|

Introduction

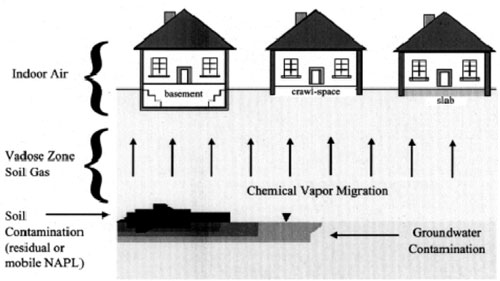

Contamination of indoor air by volatile chemicals from contaminated soil and groundwater is an emerging

area of public health concern. Vapor intrusion occurs when contaminants vaporize and rise up through

cracks, gaps, or pores in soil and foundations into homes and other buildings. Vapor intrusion is known

to have occurred at several Superfund sites in New York State and has the potential to be a problem at

brownfield sites as well. While the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC)

and the Department of Health (DOH), as well as the United States Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA), have issued draft guidance pertaining to various aspects of vapor intrusion, none have been

finalized.

On November 15, 2004 the Assembly Environmental Conservation Committee convened a public

hearing in Endicott, New York to examine issues concerning vaporization and resulting human

exposure. The primary purpose of the hearing was to determine what lessons can be learned from

past experience in order to properly address vapor intrusion in the future. The Committee received

testimony from panels of witnesses including federal, state and local government officials,

public health and environmental experts, and citizens representing affected communities.

This report provides a summary of testimony received at the hearing and recommendations for

future action.

Background

While federal and state agencies have been aware of the potential for vaporized contaminants to enter into

homes and buildings for over a decade, conventional wisdom held that levels of indoor air contamination

would not be of concern due to dilution and attenuation. Experts in environmental health and engineering

have only recently come to realize the true potential for vapor intrusion to result in widespread human

exposures. Indoor air sampling performed at a site in Colorado in 2000-2001 found significant levels

of the contaminant trichloroethylene (TCE) in homes where the computer model recommended by EPA

had predicted little or no contamination. As a result, EPA and state agencies began a national effort to

understand vapor intrusion and to revisit sites where cleanup has occurred but the potential for vapor

intrusion is high.

Here in New York, this effort led to the discovery of widespread contamination in Endicott, which now

has mitigation systems in place in over 450 homes and businesses. Vapor intrusion has also been

discovered in Hopewell Junction, which EPA proposed for listing on the National Priorities List (NPL)

on September 23, 2004 pursuant to federal Superfund. At Hopewell, EPA collected soil gas samples

at 206 homes and found detectable concentrations of TCE at 65 of those homes. Sub-slab ventilation

systems have been installed at 42 of the 65 homes. Vapor intrusion problems have also been identified

in Hillcrest, at the Jackson Steel site in Long Island, at the Morse Industrial Corporation site in Ithaca,

as well as at several other sites around the state.

The issue of vapor intrusion poses serious challenges for sound public policy making in New York

State as well as nationally. The biggest of these challenges is the lack of clear health and environmental

standards for indoor air pollution. This is especially true for TCE, the most common volatile chemical found

at thousands of contaminated sites across the country. TCE is the chemical of greatest concern at the

Endicott, Hopewell Junction, and Hillcrest sites. The level of TCE contamination considered protective

of human health varies widely across EPA regions and states, causing concern to citizens and regulatory

agencies alike.

A number of other challenges posed by vapor intrusion must also be addressed. They include:

-

How to determine which sites and/or buildings have the potential to be contaminated by

vapor intrusion and should be tested;

-

Following preliminary investigations, how to determine which sites and/or buildings

have contamination problems serious enough to investigate further and/or mitigate;

-

How to proceed with the mitigation of buildings with problems;

-

Whether current mitigation systems are adequate to protect public health over the

long term, and how to ensure the proper monitoring and maintenance of such systems; and

-

Whether mitigation alone is sufficient, or whether more extensive remediation

is needed to eliminate the source of contaminants.

Status of Current Standards and Regulation

EPA is in the process of developing guidance for evaluating vapor intrusion. This guidance

was designed only to determine if there is a potential for an unacceptable risk, not to provide

recommendations on how to delineate the extent of risk or how to eliminate the risk. The

guidance will not resolve the lack of national standards for contaminants in indoor air. EPA’s

Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response released the draft guidance in the November 29, 2002

Federal Register and is currently reviewing the numerous comments received. Two technical sessions

have been held to review the draft guidance and a third is planned for March 2005. It is uncertain when the

guidance will be finalized.

In 2001, EPA released a draft toxicity assessment for TCE based on current information regarding toxicity

and health effects. Significantly, the draft assessment found that children are more susceptible to TCE

exposure than adults and that TCE is five to 65 times more toxic than was previously believed. The TCE

toxicity assessment was peer reviewed by EPA’s Science Advisory Board, which recommended

finalization of the assessment with some revisions. In response to concerns raised by the Department

of Defense, however, EPA requested additional external peer review by the National Academy of Sciences.

The Academy officially initiated its review of the draft assessment in December 2004. It is expected to take

about 15 months.

In the meantime, some states and EPA regions have adopted more stringent TCE exposure and remediation

guidelines based on the analysis provided in the draft assessment. In the absence of a definitive toxicity

assessment, the TCE guidelines adopted by Regions and states vary significantly, by an order of magnitude or

more. For example, EPA Regions 3 and 6 adopted TCE air guidelines based on the most conservative

assumptions provided in the draft toxicity assessment. At 0.016 micrograms per cubic meter

(mcg/m3) and 0.017 mcg/m3

respectively, these guidelines are among the most stringent in the country, and correspond to one excess lifetime

(30-year) cancer among a million people. Colorado has adopted 0.016 mcg/m3

as the level at which screening will occur and 1.6 as the level at which cleanup will be required. EPA Region 9

presented two values, 0.017 and 0.96, in their "Preliminary Remediation Goals Table" published in

October 2004. An explanation of the 2004 Table states, "Region 9 has shown both [TCE values] on this

Table, rather than choosing one over the other, to give Table users as much information as possible in the

absence of a final EPA toxicity value." The State of California has a "Target Indoor Air

Concentration" of 1.22 mcg/m3 based on a much less conservative

toxicity assumption than those contained in EPA’s draft assessment (See Appendix F for a table showing the

range of TCE values employed by various EPA Regions and states).

In October of 2003, DOH established an air guideline for TCE of 5 mcg/m3,

which is significantly higher than California, Colorado, and several EPA Regions. This guideline is the subject of

much debate, and DOH is currently in the process of establishing a panel of experts to provide peer review for the

guideline. The promulgation of the new TCE guideline has resulted in the inconsistent treatment of homes in

Endicott. Before October 2003, vent systems were installed in homes where TCE was detected at levels above

0.22 mcg/m3. However, under the new guideline, homes tested after

October 2003 only qualify for vent systems if TCE is detected at levels above the

5 mcg/m3 threshold. This has led to confusion and frustration within

the affected community.

In late 2004, DEC issued a draft Program Policy titled "Evaluating the Potential for Vapor Intrusion at Past,

Current, and Future Sites." This draft policy states that DEC has compiled a list of 400 State Superfund sites

at which chlorinated volatile organic compounds (CVOCs) have been disposed or detected in groundwater and

750 sites with groundwater contaminated by volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Under the policy, these sites would be

evaluated and ranked for further investigation and potential remediation. The public comment period on the draft policy

ended on January 24, 2005. The draft policy left several concerns that will hopefully be addressed before the policy is

finalized, including the number of sites to be investigated, how long it will take, and what level of exposure will trigger

remediation (See Appendix D for the full text of Assemblyman DiNapoli’s comments on the

draft policy).

DOH has also issued draft guidance on vapor intrusion titled "Guidance for Evaluating Soil Vapor Intrusion in

the State of New York." The draft was released on February 21, 2005. The public comment period ends

April 23, 2005.

In New York State, a new Brownfield Cleanup Program (BCP) was enacted in October of 2003. The law provided for the

voluntary cleanup of brownfield sites, refinancing of the State Superfund program, and the creation of a comprehensive

program for the long-term restoration of groundwater. Under the BCP statute a new Groundwater Protection and

Remediation Program was created, the provisions of which are based on experience under the Superfund and

Oil Spill cleanup programs. The program provides for the long-term pursuit and remediation of groundwater

contamination that has migrated off-site. The law also requires the provision of opportunities for meaningful

public participation, and establishes a Technical Assistance Grants Program for both Superfund and brownfield

sites, something that will be particularly important at vapor intrusion sites.

Summary of Testimony

The following are summaries of testimony presented at the hearing or submitted for the record.

These summaries were prepared either by the witness or by staff using their written testimony. Copies

of the written testimony may be obtained by contacting the Committee.

Honorable Maurice Hinchey, Congressman, 22nd District

This hearing is an important step towards assessing how regulatory agencies have dealt with Endicott’s

toxic contamination and how to improve procedures for dealing with the emerging threat that vapor intrusion

presents in communities statewide.

As I learned of the extensive toxic plume beneath Endicott, I immediately pushed for a comprehensive health

study as well as expedited remedial action. While progress has been made on both these fronts -- a health study

is underway and the site has been reclassified from Class 4 (site which has been properly closed but requires

continued management) to Class 2 (site which poses a significant threat to public health or the environment

and requires action) on the New York State Registry of Inactive Hazardous Waste Sites -- there is more to be

done.

Some of the unresolved issues concerning this site include:

-

Shoddy regulatory record keeping, particularly the absence of a consent order between IBM and DEC -- which

should have been established in the 1980s;

-

The positive identification of the polluter primarily responsible for releasing toxic chemicals. To date some

80,000 gallons of toxic chemicals have been removed, yet IBM has admitted to releasing only 4,100 gallons;

-

The status of the historical records reportedly maintained by IBM which track employee mortality rates; and

-

The remediation timeline and whether the Consent Order entered in August 2004 will serve as the

guiding document, or will be superceded by a Record of Decision.

TCE inhalation and drinking water standards are presently under review by the federal government.

The progress of this review should be followed closely and may have a profound impact on remediation

efforts in Endicott and elsewhere.

Honorable Joan Pulse, Mayor, Village of Endicott (Edited by staff)

The Village of Endicott has encountered numerous trials and tribulations throughout the years. Although we

have faced challenges, we were still able to seize and capitalize on every opportunity that was presented

before us.

During my campaign and since election, I have had three primary goals for the Village of Endicott: fiscal

responsibility, economic development (which will create and secure the future for our children), and safety

(specifically addressing any and all environmental concerns in our community). Protecting our community,

and holding accountable those responsible for the contamination, is fundamental to my

beliefs-THOSE WHO DID IT; CLEAN IT UP!

Five years ago, no one had ever heard of vapor intrusion. A situation in Colorado shed new light on our

understanding of vapor intrusion. EPA continues to work diligently to help others understand the

environmental impacts of this emerging issue.

State and local agencies have met with residents on numerous occasions, provided information,

conducted investigations, and where appropriate, ensured that responsible parties are held accountable

for cleanup. I, and the residents of the Village of Endicott, would accept no less. I would argue that Endicott,

from the environmental perspective, is one of the most highly scrutinized municipalities in the State, if not the

Nation.

I welcome and endorse the need to protect our citizens. I personally have said and will continue to say, "I

will hold IBM’s feet to the fire" when it comes to protecting our environment - but I refuse to accept

the portrayal by the media that every effort isn’t being made to address the situation. Yes, there are

environmental concerns in Endicott and they do need to be resolved. There needs to be oversight, to ensure the

protection of citizens - and that is being done by the DEC and the State and County DOH.

I rely on and thank the DEC and the State and County DOH. Moving forward, protecting residents, improving the

quality of life, and providing opportunities are the responsibilities of my administration. I encourage those present

to join me in accomplishing these goals, and I again thank the committee for taking up this issue.

Carl Johnson, Deputy Commissioner, Office of Air and Waste Management, NYS Department of Environmental

Conservation (Edited by staff)

Along with the New York State Department of Health (DOH), the Department of Environmental Conservation

(DEC) is committed to protecting public health and environmental quality from the potentially serious effects

of vapor intrusion into homes and businesses.

Vapor intrusion is a rapidly developing field of science and policy. While chemical concentrations of vapors

are typically low, in some instances they can accumulate to levels which pose safety hazards, including the

potential for explosions or acute health effects. Even in low concentrations, these vapors may lead to chronic

health effects.

Determining the exact concentrations of contaminants in a building resulting from vapor intrusion may be

difficult. For example, the use of other substances (including gasoline and cleaning solvents) in or around

a building may complicate our ability to effectively determine the precise level and source of contaminants

stemming from vapor intrusion. Through modeling and direct measurements, DEC makes the best possible

estimate of actual contamination levels resulting from vapor intrusion. In partnership with DOH, we then

search for means to resolve the problem.

DEC recognizes that vapor intrusion cannot be resolved simply through ventilation at the buildings where

hazardous or potentially hazardous levels of vapors are discovered. Elimination of the source is our ultimate

objective. We view the use of vapor mitigation systems as a short-term solution to the vapor intrusion problem.

By addressing the source of the contamination, and ensuring that steps are taken to remediate and monitor the

soil and groundwater which provides a pathway for the migration of these chemicals, DEC can provide effective

long-term protection of the public health from vapor migration.

The standards with which cleanups must comply are determined by DOH, not DEC. Our responsibility involves

establishing a cleanup plan which ensures that contamination is cleaned up to the level established by DOH.

DEC has developed a program policy to deal with all sites in all the remedial programs where vapor intrusion

may be an issue. The strategy in the policy divides the universe of sites into two groups: 1) sites where remedial

decisions have already been made (legacy sites) and 2) sites where remedial decisions have yet to be made.

The guidance in this document primarily applies to the first group - sites where decisions have already been

made - and outlines a process to be used to identify and prioritize those sites for further action. A prioritization

approach has been developed to focus efforts on evaluation of legacy sites with the greatest potential for vapor

intrusion first. DEC is in the process of working through the universe of legacy sites in order to identify the sites

of concern. The sites in group 2 have already been evaluated and, where necessary, vapor intrusion is being

added as part of a routine investigation. All future sites will include a vapor intrusion investigation component.

The remediation of vapor intrusion sites is complex, and these comments only provide a brief synopsis of the

actions which DEC undertakes.

Nancy Kim, Ph.D., Director, Division of Environmental Health Assessment, NYS Department of

Health (Edited by staff)

The New York State Department of Health (DOH), in conjunction with other state and federal agencies, is

carrying out a number of activities related to vapor intrusion, including the performance of environmental

health investigations and health studies; the development of remedial guidance, guidelines for chemicals

in air, and soil cleanup objectives for brownfields; and the provision of public health information.

Environmental health investigations at vapor intrusion sites follow an approach consistent with that for other

environmental media. Since no two sites are exactly alike, the approach is dependent on site specific

conditions, including site use history, geological and other physical characteristics, and potentially exposed

populations. Existing information is reviewed and new data is gathered until questions regarding current

and potential exposures and the actions needed to prevent or mitigate exposures and remediate the source

of vapor contamination can be answered.

DEC and DOH are drafting guidance right now for investigating and evaluating exposure pathways, an early

draft of which is attached to our testimony.

DOH is also developing an approach to making remedial decisions based on soil vapor and indoor air

concentrations. The approach is outlined in a matrix and to date matrices have been developed for

trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethylene. Drafts are being provided with our testimony for you to comment

on however you want to. The form of the matrix is evolving as we learn more and apply it at different sites.

In addition, DOH has developed indoor air guidelines for the drycleaning chemical tetrachloroethylene

(also known as perc), dioxin, PCBs and TCE. The TCE guideline was established after an extensive

evaluation of scientific information using methods consistent with those used by other agencies and

scientific bodies. We looked at both cancer and non-cancer effects and focused most on inhalation studies.

We developed potential guidelines or criteria for evaluating TCE toxicity for all the different health effects, and

in general, those guidelines range from one to ten micrograms per cubic meter of air. The guideline adopted

is five micrograms per cubic meter of air.

We developed the TCE guideline based on our understanding of the science. We reviewed EPA’s draft

Toxicity Assessment for TCE and the Science Advisory Board’s review, which provided many

recommendations for improving the document and many more details about the uncertainties involved

in estimating TCE’s cancer risks. Depending on the various aspects of TCE at issue, we came up

with a slightly different answer than the Assessment. We also looked at critiques of the Assessment by

some other EPA scientists who are aware of California’s work on TCE.

Some EPA regions have taken a lower figure and some reference concentrations are higher. It depends on

which guideline you look at. For example, the cancer potency factor for TCE in air recommended by EPA

Region 3 is the highest recommended by EPA in the draft Assessment. It is based on an epidemiological

study with the following limitations: the study did not have individual exposure measurements; the study

population was exposed to other chemicals besides TCE; and the routes of exposure for the study were

ingestion, and probably dermal absorption and inhalation, as compared to inhalation alone.

Our guideline corresponds to an excess cancer risk of between one in one million and one in one hundred

thousand, depending on the risk extrapolation relied upon. But it is generally probably a little bit greater than

one in one million.

We have committed to a peer review process for the TCE guideline and expect to ask various stakeholders to

recommend scientists for the peer review. For the peer review, we are completing an extensive scientific

document about the key issues related to TCE toxicity and risks. We also recognize the need to continue

to update, review and refine our evaluation of the potential health risks associated with TCE using good

science.

Matthew Hale, Director, Office of Solid Waste, US Environmental Protection Agency (Edited by Staff)

EPA considers vapor intrusion from contaminated soils or groundwater into homes and other buildings to be

a significant environmental concern and one where the science is still evolving. We have long recognized that

volatile organics contaminating soils or groundwater can migrate into nearby buildings, resulting in indoor air

levels that may present a human health threat. Within recent years, however, we have come to recognize that

the occurrence of vapor intrusion into buildings is more widespread than previously thought. For example, in

some cases, volatile organics have migrated further from their source than was expected; in others, vapor

intrusion was not originally identified as an exposure pathway of concern, but later proved to be one.

Because we now recognize the potential for vapor intrusion to be a significant exposure pathway at certain

remediation sites, EPA and state environmental agencies have paid increased attention to indoor air

concerns at cleanup sites where soil or groundwater is contaminated with volatile organics. For example,

in the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) corrective action cleanup program, we routinely

screen sites for potential vapor intrusion where there is a possible concern. Where concerns are identified,

EPA (or more frequently under RCRA, the authorized state agency) requires corrective action - for example,

the installation of vapor removal systems beneath a building.

Perhaps the most difficult challenge relating to vapor intrusion is determining with reasonable certainty

whether there is likely to be a problem or not when buildings are in the vicinity of soil or groundwater

contaminated with volatile organics. A complicating factor in evaluating vapor intrusion and the risks it may

pose is the potential presence of some of the same chemicals at or above background concentrations from

the ambient (outdoor) air and/or emission sources in the building e.g., household solvents, gasoline, cleaners.

Because of the large number of sites where vapor intrusion could potentially be a concern, because the science

is still evolving in this area, and because of the technical difficulties in determining whether there actually is a

problem at a given location, the EPA Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response developed draft screening

guidance, which it published for comment on November 29, 2002 (Federal Register November 29, 2002:

67 FR 71169-71172).

In this draft guidance, EPA recommends a tiered approach to screening sites for vapor intrusion potential - that is, to

determine whether vapor from volatile organics is likely to be entering buildings, and if so whether it would likely be a

health concern. The guidance recommends that regulators and responsible parties use a conservative modeling

approach in determining whether there is likely concern at a given location, and that they conduct sub-slab and

indoor air sampling when the possibility of vapor intrusion at levels of concern can’t be ruled out. The

guidance also notes that when indoor air sampling is conducted, that it be conducted more than once and the

sampling program be designed to identify ambient and indoor air emission sources of contaminants.

EPA received numerous comments on this guidance, which it is now reviewing. We have held technical working

sessions with the states, academia, and external stakeholders to discuss this guidance in San Diego, California

and Amherst, Massachusetts, and will be returning to San Diego next March for our third technical working session.

After that meeting, we will determine how best and over what time period to finalize the guidance.

When it published this draft guidance, EPA recommended its use at RCRA, Superfund, and Brownfield cleanup sites.

However, we emphasize that it is only guidance and is still in draft form, and that other approaches may also be

appropriate. Furthermore, the State of New York is authorized to run the RCRA cleanup program in lieu of EPA,

and therefore the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation is generally responsible for overseeing

and regulating RCRA cleanups within the state. New York-like any authorized state under RCRA-may choose to follow

this guidance, or may adopt other approaches that achieve protective results.

Joseph Graney, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Dept. of Geological Sciences and Environmental Studies, State

University of New York at Binghamton (Edited by staff)

I have been fortunate to have been involved in some of the scientific research related to the Hillcrest problems.

Much of my work at Hillcrest has been related to the emission and transport of vapor phase mercury. I believe that

similarities in the chemical and physical properties of mercury to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) may allow

findings from mercury monitoring studies to act as a potential surrogate for designing future studies of VOCs in

brownfields as well as residential exposure studies.

The methods for detecting indoor air concentrations of organic compounds such as trichloroethylene (TCE) and

other VOCs typically require use of Summa canisters and relatively long sampling times (typically 24 hours).

Collection and analysis of such samples is expensive, but needed for regulatory purposes including exposure

assessments. However, short term monitoring times and in-situ sampling methods would be of major benefit

to better determine shorter term variation in VOC concentrations from exposure perspectives. Such instrumentation

is available for monitoring low level mercury concentrations in indoor air exposure settings, and further development

of similar instrumentation for low level VOCs is needed. Such instrumentation could be used to quickly screen

large numbers of residences in a cost effective manner.

The times of year when samples should be collected for indoor and ambient air exposure assessments need

further study. I am not convinced that the major indoor air exposure to contaminants associated with vapor intrusion

occurs during the winter months (i.e. during the heating season when forced air furnaces are in operation). Sampling

during all seasons should be carried out to document temporal trends in VOC concentrations specific to the climatic

conditions in the Southern Tier of New York State.

The complex terrain of the Southern Tier (characterized by incised river valleys and surrounding hilltops) may make

ambient air quality from venting of VOCs in residential areas a concern, due to the likelihood of pollutants being

preferentially channeled within the river valleys. Methods should be devised and tested to lower the VOC emissions

to ambient air. For example, the installation of in-situ VOC vapor adsorption cartridges inside ventilation ductwork

may lower emissions to ambient air.

Groundwater contamination problems are proving to be difficult to rectify. There may be need for a further evaluation

of innovative groundwater remediation approaches above and beyond conventional pump and treat methods. The

study of preferential pathways of groundwater and vapor phase pollutant transport in relation to underground utility

services (gas, sewer, cable, electric, telephone) is also in need of further study.

Lenny Siegel, Executive Director, Center for Public Environmental Oversight

U.S. EPA’s 2001 draft toxicity assessment found that TCE is five to sixty-five times more toxic than

previously believed, largely because of the risk to children. Consequently, most EPA Regions have adopted

a new "provisional" standard of .017 micrograms per cubic meter (mcg/m3). However, New York

has no clear plan for responding at concentrations below 5 mcg/m3. Because people who live and work above

volatile pollution cannot replace the air they breathe, policy-makers should take a more precautionary approach.

Vapor intrusion is usually viewed as the rise of toxic fumes directly into structures. However, contamination may

escape over a large area, elevating ambient concentrations above the screening level. Therefore, investigations

should be based upon conceptual site models that consider all sources, pathways, and receptors.

Cleanup should be accelerated to ensure that mitigation measures will remain effective in the long run, reduce

outdoor exposures, and enable safe reuse of vapor-impacted properties. Today there are cheaper, faster technologies

that can protect against vapor intrusion and restore groundwater resources.

-

Environmental regulators should use 0.017 mcg/m3

as a screening level in their investigations.

-

Soil and groundwater cleanup goals should be strong enough to protect the air.

-

Mitigation—such as sub-slab depressurization systems—should be considered wherever sampling

shows TCE exposures above 0.17 mcg/m3 .

-

Development should be restricted wherever soil gas studies suggest that future indoor concentrations may

exceed the screening level. Where housing is approved, mitigation and notification should be required.

-

The remedy should be reconsidered at any site where vapor intrusion is recognized.

Theodore J. Henry, M.S., Toxicologist and Community Involvement Specialist, Henry and Associates, LLC

Trichloroethylene (TCE) is one of the top 8 percent most toxic compounds based on EPA Region 3 data. The data

available show that the current national debate over adequate vapor intrusion criteria is economic and not the result

of a lack of data. This is unfortunate given America’s past lessons involving lead and smoking, where we

ignored science for decades at the cost of many lives and young minds.

EPA has started addressing vapor intrusion, but investigation of this pathway is in its infancy. Furthermore, the

financial and technical expertise limitations at the state and local level will impact the Nation’s ability to

protect communities from TCE. Nevertheless, community members will try to apply political pressure where they

can to get adequate testing and remediation despite a regulatory process that is financially strapped, technically

challenged and conflicted. Some policies and regulations will be implemented to help, but this will take years and

will differ drastically from state to state. While communities work hard to bring this change, they will need the

support from political leadership to allow them to participate effectively. All participating agencies must involve

communities through HEART (Honesty, Empathy, Accessibility, Responsiveness and Transparency). Technical

issues needing to be addressed include: source definition, correlation of known contamination with records,

groundwater flow, soil gas data, indoor air data over time, biomonitoring, etc.

In the end, science must prove itself with empirical data from the affected communities, not just with modeling and

risk assessment. If the affected communities do not get this type of community involvement and technical support,

contamination will be missed, misjudgments will be made regarding true exposure levels, and the remedial actions

selected will fall short of protecting neighborhoods.

Bernadette Patrick, Citizens Acting to Restore Endicott’s Environment (Edited by staff)

I am a resident in the Town of Union and co-founder of the citizens’ action group C.A.R.E. On

October 31, 2002 my daughter at the age of 17 during her senior year of High School was diagnosed

with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

On that same day in October the DEC, DOH, and IBM representatives agreed upon a mitigation decision matrix

to be protective of public health and to be used to determine which houses in my neighborhood, located in a

300-acre toxic plume, will be eligible for a mitigation system. To date there are 480 properties with mitigation

systems installed.

-

What about those properties that did not meet the criteria? People continue to live in their homes and work in

buildings that are contaminated with VOCs. They have chemical vapors inside and under their homes but

the levels are not high enough to warrant a mitigation system.

-

What about the family with small children living next door to a vented home? They are told they don’t

need testing because they are not in the plume, they just border it.

-

What about the home in the plume that has been tested, and VOCs are detected in the sub slab and indoor air.

They are denied a system, but their neighbors all have them.

-

What about the people that live within 100 feet of the plume, that are just plain scared? What type of standard is

available to protect them? They have every reason to be concerned. They are not eligible for testing.

There are hundreds of people in this community that share these same stories. What is worse, knowing or not

knowing? The level of fear and anxiety is the same for everyone living within this plume. Test or no test, system

or no system.

Think about the scenarios I just mentioned. They are real. There are about 200 more homes in the area near

the mapped plume that have TCE under them. They are not qualifying for testing or mitigation systems. The

only way we can ensure the safety of the people in this designated area is to lower the acceptable levels of TCE

vapor intrusion and vent their homes.

Based on this testimony I am here today asking that the EPA set a standard for TCE at nothing greater than .017

micrograms per cubic meter. It is your fiduciary duty to ensure that this community and every community nationwide

be protected from vapor intrusion stemming from soil and groundwater contamination caused by industries that

jeopardize our health and well being.

Alan Turnbull, Coordinator, Resident Action Group of Endicott (Edited by staff)

Some two years ago, my wife was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, a cancer of the throat.

Oncologists will never venture any statement as to its cause, but it is generally thought to have origins

by inhalation of air or drinking of liquids (water). In an effort to determine what may have caused this

illness, I began to ask questions from a multitude of sources, such as the Cancer Society, the

NYS-DOH, and private oncologists. Needless to say, I was confronted with more questions than

answers. To my dismay, I found that there were no safe guidelines or standards that addressed

residential indoor air standards for toxic intrusions. Therefore, safe guidelines and standards

must be established to protect the citizenship of our community as well as other communities

around the country. These guidelines and standards must be put into place as soon as possible to

ensure productive and healthy lives for all.

It is crucial that a commission of scientists and medical personnel undertake extended studies for

low dose ingestion of toxins in humans without delay. Results of this toxic/human hypothesis of low

dose exposure must be made available to the general public at the earliest timeframe possible.

Pressure should be placed on EPA to have their science committees present the lowest possible

threshold level for remediation. While some scientists admit that any air/vapor TCE reading qualifies

to institute remediation, we must not accept any guideline threshold level higher than .175 micrograms

per cubic meter (a guideline of .017 micrograms per cubic meter would be preferable).

Remediation must be vigorously undertaken by any and all means at our disposal. However,

mitigation via venting systems installed in homesteads is, at best, only a temporary "stop-gap"

measure.

Last, and most importantly, I request that the following be given serious consideration: That in order to

expedite residential VOC/toxic testing by the NYS-DOH/NYS-DEC to determine toxicology levels:

-

Sub-slab testing alone be done to determine "hotspots" of TCE/PCE within

a given area, and that a reasonable guideline be determined as a threshold of concern.

-

Readings over and above the established sub-slab threshold be scheduled for further

comprehensive testing during the heating season.

As it now stands, a team of technicians must take an inventory of any and all items within a

basement to remove anything that would possibly influence air sampling. This elimination

process alone takes approximately four hours. Thus the team is able to test approximately

two residences per day. However, by performing sub-slab sampling, approximately six houses

could be accomplished per day. By reducing time, costs would likewise be reduced, and overall

area testing would be accelerated.

Donna Lupardo, Resident Action Group of Endicott (Edited by staff)

The residents of the Village of Endicott and surrounding entities have been exposed to contaminants from

multiple exposure routes including air pollution, contaminated drinking and bathing water, soil gas, and

vapor intrusion. Health studies need to take into consideration the combined effects of these various

exposure routes. In looking at places like Endicott, there is a need to create models that take all of these

routes into consideration.

As far back as 1989, reports were being published indicating that the IBM facility led the United States

in chlorofluorocarbon emissions and other pollutants. Most of us here are interested in knowing what

the current emission levels are from the plant; how the current ambient air is affected by hundreds of

venting units; and what we can learn from historic air emission levels. After much delay, the Agency for

Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) is now in the process of surveying residents to gather

information about the historic pre-1987 air emission levels where there seems to be some kind of

information gap.

We’ve now been witness to the evolution of the science of vapor intrusion. Communities

around the State are grappling with the reality of this new exposure route. I join my friends in saying

that we want the State to thoroughly examine the issue of putting in place stricter TCE air standards,

which should be stricter than the current standard of five micrograms per cubic meter.

Many of these standards are set for adults over short exposure time periods. We’re especially

concerned that the standards also take into consideration young children who are more sensitive to

contaminants of this kind.

I’d like to point your attention to something that our Press and Sun Bulletin reported back in

August. They reported that water samples from a well installed in the IBM cafeteria building back in

1963 showed evidence of pollution in the bedrock two hundred and fifty feet below the site and evidence

suggests industrial solvents may have reached a deep aquifer that feeds a network of wells along the

Susquehanna River Valley. Collectively these wells serve at least eighty thousand residents in Vestal,

Johnson City and in Endicott. Obviously, there could be a potential need for more aggressive

remediation efforts given the sheer number of people affected.

Finally, we are grateful that ATSDR has a mixtures work group investigating the water contamination

issue. While we’ve been assured that there are low levels of various compounds in the water,

what is not clear is what happens when these low levels interact with one another. Further scientific

inquiry may show that such commingling of these contaminants represents a potential threat to public

health.

Bruce K. Oldfield, Hillcrest Environmental Action Team (edited by staff)

I am a resident in Hillcrest, NY and part of a citizens’ action group, the Hillcrest

Environmental Action Team, HEAT.

In 1992, a discharge of TCE into a dry well at the former Singer-Link facility (now owned

by CAE Electronics) was mapped, indicating movement of this material into the surrounding

neighborhood. Since then, TCE has spread throughout portions of the residential area and

even shows up in a monitoring well 1700 feet from the source, on a direct path towards our

drinking water well field.

Recently, the DEC began monitoring TCE levels in our homes. Levels above 5 micrograms/cubic

meter were discovered. I had been following a similar problem in Endicott and was told that the

standard for mitigation there was 0.22 micrograms/cubic meter. In Endicott, just under 500 homes

were vented. In Hillcrest, only three homes were vented although many more were above the

.22 micrograms/cubic meter action level used in Endicott.

The EPA proposed guideline for TCE in residential buildings is 0.017 micrograms/cubic meter.

This is roughly 300 times lower, that is, more stringent, than the standard set by New York’s

DOH. Although the DOH acknowledges the range of estimates for TCE (for one excess cancer per

million persons) is 0.2 to 4 micrograms/cubic meter, our standard was set arbitrarily higher at

5 micrograms/cubic meter. The orders of magnitude difference between the provisional EPA

standard and DOH standard concerns me and many of my fellow residents.

I am also concerned that the venting of TCE from the subslab of our homes is moving the

pollutant from one area to the next. When temperature inversions form in these valleys, the air that

we are venting from the ground is trapped in the valley so not only are we breathing it in our homes,

we are breathing it in the outdoor air also. We find this unacceptable.

I would like the NYS Assembly to consider using its influence on the NYS Department of Health to

change the NYS standards for TCE in our homes to match the EPA provisional guidelines. I would

also like to see outdoor air standards set that are going to insure that breathing this air is safe for

our children.

Debra Hall, Hopewell Junction Citizens for Clean Water

All I know is that living in the United States, paying my taxes and living an honest life, the least my

family and I deserve is clean air to breath and clean water to drink. Imagine knowing that your water

and air are contaminated. You go to the health agencies, the so called experts, who are there to help

you. But instead of getting the help you need you get untruths and false information. And then you

ask why? Is it financial? Is it that if the person tells you what they know they will get in trouble? Is

it that they really do not know?

Whatever the reason is, my family should not be at risk of getting cancer or some other deadly

disease. I see it all around me, so many sick people, especially children. It has been known that

my site was contaminated since 1979, but the correct investigation never took place. The Hopewell

Junction Citizens for Clean Water ask to stop making us victims. Give us air standards that will

protect us. It can be done. It’s possible. No more excuses. The technology is here.

It’s only common sense that this issue gets dealt with correctly and morally.

Philip J. Landrigan, M.D., M.P.P, Director, Center for Children’s Health and the Environment, Mount

Sinai School of Medicine

and

Leonardo Trasande, M.D., M.S., Assistant Director, Center for Children’s Health and the

Environment, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (Edited by staff)

TCE is an organic chemical that has been used for dry cleaning, metal degreasing and as a solvent for

oils and resins. It evaporates easily in the open air but can stay in the soil and groundwater for years

afterwards. In the body, TCE may break down into multiple other chemicals such as dichloroacetic acid,

trichloroacetic acid, chloral hydrate, and 2-chloroacetaldehyde. These products have been shown to be

toxic to animals and are probably toxic to humans, especially young children with developing bodies.

The most well-studied and significant health effect of TCE is its link to cancer. Studies of workers exposed

to TCE are sometimes complicated to interpret because many of these workers are exposed to other

solvents that also can cause health effects. However, TCE has been found to cause cancer in both mice

and rats, which suggests that it also causes cancer in humans. The World Health Organization has

classified TCE as a Class IIA carcinogen, meaning that TCE is probably carcinogenic to humans. The

EPA has also stated that TCE may have the potential to cause cancer in humans, and has set a maximum

contaminant level for TCE of five parts per million in drinking water.

Other effects that can result from heavy TCE exposure include damage to the liver, kidneys, gastrointestinal

system, and skin. TCE has been linked to birth defects. Chronic exposure to TCE can also affect the human

central nervous system. Case reports of intermediate and chronic occupational exposures included effects

such as dizziness, headache, sleepiness, nausea, confusion, blurred vision, facial numbness, and weakness.

For all of these reasons, all occupational exposures to TCE should be thoroughly investigated. Not only

do the workers who have been exposed to TCE deserve to know the potential health effects they have

suffered, but further research into the health effects of TCE will help clarify important questions that remain

about its health effects.

In addition, we also need to consider the effects of TCE contamination on people in the broader community.

For example, children are especially vulnerable to the health effects of TCE, just as they are to many other

chemicals. The health and economic consequences of children’s present-day exposures to

environmental toxicants will be experienced by our society throughout much of the twenty-first century.

Unfortunately, we have learned this lesson the hard way, in part because of exposures to chemicals such as

TCE. A very high rate of childhood cancers in Toms River, New Jersey was found to be linked to the amount

of drinking water that women ingested during their pregnancies. Even though the water was never found to

have levels higher than EPA’s contamination standard for TCE, the researchers’ analysis

demonstrated that exposure to TCE in the fetus was associated with cancer, especially leukemia, in these

children. The epidemiologists who studied this cluster of cancer suggested that the developing fetus might

be especially vulnerable to TCE and other chemicals that were found in the drinking water in Toms River. As

the exposure to TCE was removed, researchers found that the cancer rates in Toms River decreased

significantly.

One way to prevent and treat children’s exposures to environmental contaminants, such as TCE, is

through the development of a statewide system of Children’s Environmental Health Centers of

Excellence.

David Ozonoff, M.D., M.P.H., Professor of Environmental Health, Boston University School of

Public Health (Edited by staff)

I have had a long interest in the health effects of the chlorinated ethylenes TCE and its very close relative,

tetrachloroethylene (PCE), and have authored numerous peer-reviewed epidemiological studies on these

chemicals. TCE has been implicated in at least four kinds of adverse health effects: effects on the central

nervous system; cancer; birth defects; and autoimmune disease, such as lupus. For historical reasons

and force of circumstance much of our knowledge of the effects of TCE are based on occupational

exposures. While it is not easy to determine what effects might be expected, if any, at the substantially

lower levels normally encountered from vapor intrusion, I am concerned about effects even at these levels

for two main reasons.

First, we have been studying the effects of TCE in drinking water for almost 15 years and have seen

substantial increased cancer risks at exposures orders of magnitude lower than occupational exposures.

Residential exposures to drinking water come from a combination of ingestion, inhalation (from air stripping)

and dermal absorption, with the latter two being of roughly the same order of magnitude as ingestion.

The current maximum contaminant limit (MCL) for drinking water is 5 micrograms per liter. This

corresponds (roughly) to an indoor air exposure of 1 microgram per cubic meter of air. The MCL is an

old standard based on outdated cancer estimates. Thus the level of 5 micrograms per cubic meter

proposed by the NYS DOH is not consistent with the current (now fairly old) water standard.

In addition, there is reason to believe that the exposure level corresponding to an excess cancer risk

of one in one million is considerably lower than previously thought. To be health protective one normally

chooses the most conservative estimates. Considerable uncertainty in the correct parameter estimates

for important physiological processes, like the rate of absorption between species, can lead to very large

differences in dose-response modeling. W.J. Cronin and colleagues use Monte Carlo analysis in

conjunction with physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to determine the impact of

different parameter values on estimates of the risks posed by TCE. There is a wide range of legitimate

estimates using PBPK models when coupled with the linearized multistage model used by DOH. Cronin,

for example, has estimates as low as 0.02 micrograms per cubic meter as the one in one million risk for

TCE in air.

The choice of a linearized multistage model, as used by DOH, is not the only possible choice, and

choosing a different biologically plausible model can result in a large variation in estimated risks. C.R.

Cothern and colleagues investigated the variations between four different models, including the model

chosen by DOH. The difference in estimated risks among the models was almost a factor of 10,000, i.e.

the most protective model (the Weibull model) predicted risks from TCE in drinking water to be 10,000 times

higher than the risks from the least protective model (the multistage model chosen by DOH). There are no

biologically based criteria for choosing one model over another.

My second concern is that adverse health effects can be expected to result from extremely tiny exposures

where some kind of biological amplification of damage occurs. The classic example is cancer, where a

tiny alteration in DNA makes a cell into a cancer cell. The original damage is biologically reproduced and

the offending tiny amount of chemical no longer need be present. This is essentially the reason we believe

there is some cancer risk at every level of exposure.

There are other biological systems where such intrinsic amplification might be expected, including the

immune system (eg. bee stings and the dramatic, sometimes fatal effect of tiny exposures); the nervous

system (where tiny signals are amplified into large responses); and human reproduction (where an entire

organism comes from a single fertilized egg). Thus the health effects seen in occupational environments

are plausibly present, although at a much lesser frequency, at much lower exposures as well.

Daniel Wartenberg, Ph.D., M.S., Director, Division of Environmental Epidemiology, Robert Wood Johnson

Medical School (Edited by staff)

I have been studying the health effects of TCE for about 8 years and am increasingly concerned about the likely

carcinogenicity of TCE and its impact on the health of those exposed to even low levels of this chemical.

In 1997 I was awarded a grant by the EPA to evaluate the epidemiologic evidence for making inferences of

cancer hazards and risks for exposure to TCE. With colleagues, I conducted a detailed review of more than

80 relevant scientific publications. We concluded that evidence of excess cancer rates among occupational

cohorts with the most rigorous exposure assessment is found for kidney cancer, liver cancer,

non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, cervical cancer, Hodgkin’s disease, and multiple myeloma.

In 2000, I again summarized the data and made similar conclusions. One notable report published since

my review in 2000 was on a new cohort in Denmark that uses measures of biological material to document

exposure to TCE. In general, the results of that study provided additional support for the findings we

presented in 2000, which suggested that TCE exposure causes cancer in humans.

I acknowledge the limitations of some of these studies, and imprecision of the assessments of exposures,

but I believe that the evidence points strongly towards carcinogenicity and that exposure should be minimized

to the degree reasonably possible unless and until evidence to the contrary can be developed. In short, based

on the evidence, we believe that TCE should be considered a human carcinogen until proven otherwise.

In general, any exposure to a carcinogen increases an individual’s risk of developing cancer. Therefore,

on the basis of the available evidence, and in the interest of preventing unnecessary cases of cancer, I urge you to

limit exposures to the minimum amounts reasonably achievable.

Because the studies conducted did not collect sufficient data on length and magnitude of exposures for

rigorous modeling of the likely carcinogen, we should err on the side of overprotection rather than underprotection.

In addition, the research on other outcomes is somewhat limited, again suggesting the need for more stringent

rather than less stringent exposure limits.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The evidence gathered through this hearing underscores the high level of uncertainty and controversy

associated with all of the issues raised by vapor intrusion including the screening and testing of sites,

the setting of indoor air quality standards, and determining the appropriate mitigation, and remediation

measures. Policies and guidelines to address these issues are still in the developmental stage in New

York State and across the country.

An overarching principle to remember as New York proceeds to address the challenges posed by

vapor intrusion is that the degree of uncertainty associated with these challenges is an issue in itself.

Living with uncertainty is one of the most difficult aspects of living at a contaminated site. It is a source

of incredible stress and frustration. This uncertainty is a given, at least for the foreseeable future. In the

face of such uncertainty, government must strive to take a precautionary and transparent approach.

A precautionary approach holds that where threats of harm to human health or the environment exist,

lack of full scientific certainty about cause and effect should not be viewed as sufficient reason for

government to postpone precautionary measures to protect public health and the environment. We

must use the knowledge we have today to take a preventive approach to eliminating exposures from

vapor intrusion.

Government must also provide citizens with complete and accurate information on the potential health

and environmental impacts associated with different policy choices. The policy making process should

be open and transparent, and provide citizens with opportunities for meaningful participation.

In addition, the degree of scientific complexity associated with a decision should not be used to obscure

the nature of the decision at hand. For example, the scientific evidence regarding TCE supports a range

of toxicity estimates, largely based on the protectiveness of underlying assumptions. This has led to the

adoption of indoor air guidelines by EPA Regions and states that vary by an order of magnitude or more.

These guidelines are all scientifically plausible and supported by "sound science." The

choice between them is largely a policy choice, not one of science alone.

The following recommendations are based on information gathered through this hearing. These actions

should be taken as part of developing a comprehensive policy for addressing vapor intrusion in New York

State:

-

DOH should revise its TCE Guideline to reflect the most protective (i.e. conservative) assumptions

about toxicity and exposure supported by science. Where uncertainty exists, DOH should err on the

side of protection. The TCE Guideline should correspond with an excess cancer risk of one-in-one-million

as required for the development of soil cleanup standards under the BCP, based on these conservative

assumptions. Also as required in the BCP, the Guideline should be protective of sensitive populations,

especially children, and take exposure from multiple sources and routes into account. In addition, the

Guideline should be fully protective (corresponding to a hazard index of one) for all non-cancer health

effects as identified by the Department in its own risk assessment.

-

Residents living adjacent to or near a contaminated site with a potential for vapor intrusion, but

outside the perimeter of the area that has been designated to be tested, have legitimate concerns

regarding whether contamination is present in their homes. At a cost of two thousand dollars or more,

testing represents a large cost to these residents but only a small percentage of the overall cost of

cleaning up the site by the responsible party or the state. In such instances, DEC and DOH should

test the indoor air of any resident who requests such a test.

-

DEC should continue to review and improve the methods used to screen and investigate sites,

including sampling during all seasons of the year and taking into account preferential pathways.

-

DEC should take steps to protect ambient air quality at vapor intrusion sites, including the adoption

of requirements that would limit the emission of contaminants to ambient air from indoor air

mitigation systems.

-

When development is approved at sites with the potential for vapor intrusion problems, long-term

monitoring and mitigation should be required. In addition, potential owners, tenants, and other

long-term users of the site should be notified of the potential for vapor intrusion problems prior to

sale or entering into a contract.

-

Once direct exposures have been mitigated, focus should be placed on cleaning up the source of

vapor intrusion, i.e. soil and groundwater contamination, as quickly and aggressively as possible.

DEC’s view of mitigation as a short term solution and their stated intention to ensure that

steps are taken to remediate soil and groundwater and eliminate the source of hazardous vapors

should be strongly supported. Furthermore, in promulgating generic soil cleanup standards

pursuant to the BCP statute, DEC, in consultation with DOH, must take vapor intrusion into

consideration.

New York State is in the beginning stages of developing policies to address vapor intrusion and should

work with citizens and public policy makers to tackle the important challenges ahead in addressing the

threat to public health posed by vapor intrusion. This hearing was one effort to provide transparency and

encourage participation.

|