|

||

|

Scott M. Stringer, Chairman

|

|

Roger L. Green, Chairman

|

|

March, 2001 |

||

|

|

|

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This investigation involved the input of many people. The Committee Chairs, William L. Parment and subsequently Scott M. Stringer, and Roger L. Green, provided guidance and direction to Committee staff throughout. Much of the research was conducted under the leadership of Assemblyman Parment, former Chair of the Committee on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation. In January 2001, Assemblyman Stringer took over as Committee Chair. Along with Children and Families Committee Chairman Green, Chairman Stringer has assumed the task of completing this report, implementing its recommendations, and helping to ensure ongoing legislative oversight of the CONNECTIONS project. Assemblywoman Susan John, former Chair of the Governmental Operations Committee, also offered critical insights during the Committees' public hearings. The principal researcher and report drafter was Virginia Rosenbloom, Policy Analyst with the Oversight Committee. Her work included reviewing thousands of pages of procurement documents, analyzing financial information, and meeting with Administration personnel and other stakeholders. Andrea Zaretzki, Executive Director of the Oversight Committee, provided vital insight, direction and editorial support, from the investigation's inception through report completion. A number of Oversight Committee staff played key roles. Committee Counsel Tom Fox provided legal guidance, including assistance in developing the report's legislative recommendations. Policy Analyst Mark Hennessey conducted research and data analysis, and provided technical support. Michael Benjamin, Senior Legislative Associate, and Ralph Kulseng, former Committee Senior Policy Analyst, also helped out with research. All Committee staff played significant roles in preparing and presenting materials for the public hearings. Other Assembly staff who contributed at various stages of the project included: Joanne Barker, Maria Torro, Mitzi Glenn, Sania Metzger, Eva Pierce, Beth Harbour, Linda Ashline, Julie Ruttan, Pat Fahy and Kris T. Reape. Additional input and guidance was provided by John Hudder, Janet Mannella, and Roman Hedges. The Committees wish to acknowledge the cooperation and support received from the staff of the Governor's Office and the Office of Children and Family Services throughout this examination. The staff of the Office of State Comptroller also provided expertise and information critical in this effort. Thanks to all. |

|

|

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

APPENDIXAbbreviations Used in this Report |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A. PURPOSE OF THE INVESTIGATION

This report examines the procurement, development, and impact on children and families of the Office of Children and Family Services'1 CONNECTIONS computer system. This system was the State's answer to a 1993 federal law which encouraged states to create Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information Systems (SACWIS). It was intended to track the tens of thousands of children receiving various child welfare services across New York State. CONNECTIONS was also designed to connect the State agency with the counties and not-for-profit agencies that provide these services. The Committees' interest in CONNECTIONS is two-fold. First, the Assembly Committees on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation and on Children and Families had previously identified problems with the CONNECTIONS system as a result of their earlier examination of the State's foster care system. Some of these problems were documented in the Committees' May 1999 report LOSING OUR CHILDREN: An Examination of New York's Foster Care System. The current investigation was intended to follow up on issues raised about CONNECTIONS during that earlier study. In addition, the Committee on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation focused on the CONNECTIONS procurement as part of its broader examination of New York's computer technology procurement practices. CONNECTIONS is one of the largest information technology projects undertaken by the State (the cost of the project overall has grown to over $362 million). Together, the two main contracts the State entered into to build the system place CONNECTIONS in the top ten most expensive procurements covered by the Procurement Stewardship Act.2 This report presents the Committees' findings, including quotes from system users and relevant documents. It also makes recommendations applicable to CONNECTIONS specifically, as well as for improving the State's information technology procurement process generally. It is the Committees' hope that similar problems will be avoided in other large current and future computer system projects.

B. BACKGROUND ON CONNECTIONS

When the original contracts for the system were announced in 1996, Governor Pataki expressed high hopes for it:

Yet five years later, the two main contracts have grown from $113.6 million to $216 million, only three out of five major components of the system are operational, and users complain that these parts do not work as intended and are unreliable. The case management portions of the system -- designed to keep track of children receiving services -- is not in place, and a system to enable local reporting is not expected to be available statewide until the end of 2001 at the earliest. Caseworkers on the front lines report that the system actually increases their administrative time rather than decreases it. They fear that children may continue to be at risk of abuse and neglect because of the inadequacies of CONNECTIONS. In the words of Maximus, the contractor recently hired by the State to recommend how to fix CONNECTIONS' problems:

Maximus is conducting an entire re-assessment of CONNECTIONS' hardware and software. It is expected to recommend either fixing the components that have not been rolled out because they do not meet users' needs, or scrapping them and starting from scratch. At an Assembly hearing in May 2000, Marjorie McLoughlin, Executive Director of Cardinal McCloskey Services -- a not-for-profit child welfare agency under contract with New York City -- told the Committees that her agency has been less able to serve the client population as a result of CONNECTIONS. She summed up her complaints with the system:

Nicholas Scoppetta, Commissioner of New York City's Administration for Children's Services (ACS), also expressed dissatisfaction with the system's ability to meet expectations:

Chautauqua County Social Services Commissioner Edwin Miner tied CONNECTIONS' inadequacies to a lack of proper vision and project planning:

As recently as January 2001, the successful plaintiffs in an action brought against New York City and New York State argued that CONNECTIONS' failings hurt children and taxpayers, and that continued court intervention was needed:

C. OVERVIEW OF THE STUDY

Much of the research involved in this investigation was conducted in 1999 and 2000 under the leadership of William L. Parment, then-Chairman of the Oversight, Analysis and Investigation Committee. In January 2001, Assemblyman Scott M. Stringer took over as Chairman of the Committee. He has joined Assemblyman Roger L. Green, Chairman of the Committee on Children and Families in completing the report, implementing its recommendations, and helping to ensure ongoing Legislative oversight of the CONNECTIONS project. Between the fall of 1999 and the spring of 2000, Oversight Committee staff examined the procurement record and related documents, spoke to State Comptroller and agency personnel, and reviewed various outside reports that cite CONNECTIONS. Joint public hearings were held by the Assembly Committees on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation, on Children and Families, and on Governmental Operations in May 2000. Testimony was received from various users of the system, including not-for-profit child welfare agencies, county social services commissioners, and unions representing State and county workers who use the system, as well as the State Comptroller, the contractors, and representatives from the Administration. The investigation focused on the following issues:

This report brings together key issues and findings identified during the Committees' investigation. Summarized below are the key findings raised in the report, as well as administrative and legislative recommendations. It is important that the Administration act quickly to complete the implementation of a properly functioning statewide child welfare information system. Until then, children may continue to be at an increased risk of abuse or neglect, costs will continue to rise, services will suffer, and the implementation of major child welfare programs will be hampered. Such programs include the federal Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA) and New York City's Neighborhood-Based Child Welfare Services initiative. While the Administration has made recent efforts to solicit the needs of system users and to reassess the system as a whole, more needs to be done, and quickly.

D. FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

PROBLEMS WITH THE CONNECTIONS SYSTEM AND THEIR IMPACTS ON CHILDREN AND FAMILIES Findings

Recommendations Administrative

Legislative

PROCUREMENT ISSUES Findings

Recommendations Administrative

Legislative

CONTRACT MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION Findings

Recommendations Administrative

FISCAL IMPACTS Findings

Recommendations Administrative

Legislative

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This report examines the procurement, development, and impact on children and families of the Office of Children and Family Services' CONNECTIONS computer system. This system was intended to track children receiving various child welfare services across New York State. CONNECTIONS was also designed to connect the State agency with the counties and not-for-profit agencies that provide these services. Data from the Office of Children and Family Services show that in 1999, 138,000 reports of child abuse or neglect were received by the State Central Registry of Child Abuse and Maltreatment; 42,000 children received preventive services; 47,700 children were in foster care at year end; and 3,400 were legally freed for adoption.12 So far, CONNECTIONS tracks information only on the children included in the child protective reports received by the Registry. Until CONNECTIONS is fully implemented, children receiving the other child welfare services are tracked in the State's old systems or in manual systems. The report identifies numerous problems with the procurement, development and implementation of the CONNECTIONS system. It makes recommendations that are both specific to CONNECTIONS and also can be applied systemically, with the hope of avoiding similar situations in the future.

The Committees' interest in CONNECTIONS is twofold. First, the Assembly Committees on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation and on Children and Families had previously identified problems with CONNECTIONS as a result of their earlier examination of the State's foster care system. Some of these problems were documented in the Committees' May 1999 report LOSING OUR CHILDREN: An Examination of New York's Foster Care System. Since then, other sources have pointed to continuing problems with the system, including State Comptroller audits, the federal Health and Human Services Inspector General, and numerous newspaper accounts in which local governments and not-for-profit agencies voiced complaints. The Committees' current investigation was intended to follow up on the issues raised about CONNECTIONS. In addition, in the spring of 1999, the Assembly Standing Committee on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation initiated a broader examination of New York's computer technology procurement practices, to determine whether they are fair, effective and cost-efficient. At the time, the purchase of computers and information technology, as well as other goods and services purchased by State agencies, was governed by the State Procurement Stewardship Act of 1995 (the Act), which was due to sunset June 30, 2000. The Act has since been modified and extended until June 30, 2005. Certain provisions relating to information technology have changed, and will be discussed in this report. The Committee focused on information technology contracts because of the large number and cost of computer projects undertaken by State agencies in recent years. Since 1995, the cost of information technology contracts as a percent of all contracts covered by the Act has more than doubled from 7% to 17%. At the end of State fiscal year 1995-1996, the State had entered into information technology contracts worth $1.3 billion. By the end of State fiscal year 1999-2000, this investment had more than tripled to $4.6 billion.13 As part of its broader examination, the Committee examined several key information technology contracts entered into pursuant to the Act. Of particular interest were those which have had bid protests lodged against them by unsuccessful bidders, which might indicate problems with the procurement process. Among these projects was CONNECTIONS. CONNECTIONS is one of the largest information technology projects undertaken by the State (the cost of the project overall has grown to over $362 million). Together, the two main contracts with outside vendors that the State entered into to build the system place CONNECTIONS in the top ten most expensive procurements covered by the Act. These contracts now total $216 million of the$362 million total cost of the project to date. When the original contracts to build CONNECTIONS were announced in 1996, Governor Pataki expressed high hopes for it:

Then-Acting Commissioner Brian Wing of the Department of Social Services, the agency responsible for the project at the time, predicted:

Yet five years later the system does not work as intended and contract costs have escalated from $113.6 million to $216 million. Caseworkers on the front lines report that the system actually increases their administrative time spent rather than decreases it. They fear that children may continue to be at risk of abuse and neglect because of the inadequacies of CONNECTIONS.

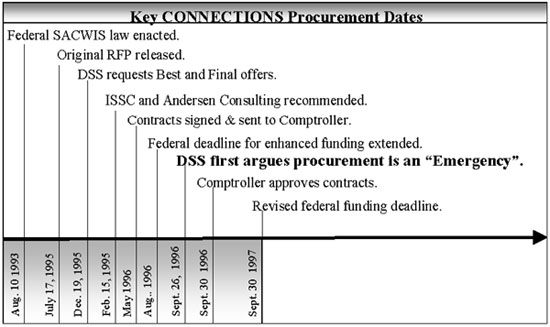

CONNECTIONS is New York State's response to a 1993 federal law16 which encouraged states to create Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information Systems (SACWIS) to provide for effective management, tracking, and reporting of children in the child welfare system. Enhanced federal reimbursement of 75% was originally available through September 1996 for the planning, design, development and installation of the system. Operational costs were to be reimbursed at a rate of 50%. After the 1996 deadline, expenses covered by enhanced funding would drop to the lower 50% rate as well. The deadline for enhanced reimbursement was later extended through September 1997. New York intended its system to meet the requirements of the federal Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). AFCARS requires states to report certain statistics on children receiving foster care and adoption services to the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) or face penalties, starting in 1997. AFCARS compliance was a key goal of the CONNECTIONS system and part of the Request for Proposals (RFP). The CONNECTIONS system was intended to serve as an important information system to help track the thousands of children in the State's child welfare system. It was designed to address a growing crisis in child welfare in New York, where children were falling through the cracks in the "system". Among its goals were to:

The Department of Social Services (DSS) released the Request for Proposals (RFP) in July 1995. In February 1996, in a rush to meet the original federal funding deadline, DSS awarded contracts to two vendors: ISSC--a subsidiary of IBM--for hardware installation, and Andersen Consulting LLP for software development.18 Together, the original contracts totaled $113.6 million. Five years later, the contracts have grown to over $216 million, only three out of five major components of the system are operational, and users complain that these parts do not work as intended and are unreliable. Caseworkers say it has created more work for them, rather than assisting them to do their jobs, and as a result, they have less time to spend with children. Only part of the system is operational, and there is a general lack of confidence in the components that are in place. Local child welfare agencies have, therefore, created workarounds and separate systems, and continue to maintain paper files. At an Assembly hearing in May 2000, Marjorie McLoughlin, Executive Director of Cardinal McCloskey Services, a not-for-profit child welfare agency under contract with New York City, summed up her agency's complaints with the system:

Software implementation began in 1996. The system was originally to be comprised of five "releases", which supported various child welfare services. However, implementation was halted in early 1998 when users complained that the largest component, "Release 4", which was supposed to handle case management and fiscal management, did not meet their needs, was time consuming, and had many technical problems. Release 4 was never implemented; neither was Release 5 which was to provide management reports to local child welfare supervisors. Later that year, a State Comptroller audit of the system found weaknesses in the planning, design, development, and implementation of the system, as well as poor controls over change orders. In response to the audit, the Governor convened a Review and Oversight Panel in January 1999 to review the project and make recommendations for proceeding. The Panel's recommendations included hiring a consultant -- known as a Project Integrator -- to monitor and evaluate fixes to the system being done by State workers and Andersen Consulting. The consultant was also to conduct a reassessment of the entire system to determine whether and how to either fix it, or scrap it and start over. The Office of Children and Family Services, which is now responsible for the project, has also formed various management committees and user groups to involve users of the system in developing the final product. While most users are generally optimistic about the recent plans for re-evaluating and fixing the system -- and virtually all agree that such a system is urgently needed in New York -- they continue to maintain duplicate manual records and alternative computer systems because they do not believe CONNECTIONS is reliable.

C. NEW YORK'S CHILD WELFARE SYSTEM New York's child welfare system serves tens of thousands of children statewide receiving child protective services, preventive services, foster care services, and adoption services. These programs are administered locally by social service districts in 57 counties and New York City. Some local districts contract with private not-for-profit agencies to provide certain services. Unlike many other states, New York has a decentralized system; the State agency serves primarily in an oversight and advisory capacity. Until January 1998, the former New York State Department of Social Services (DSS) was responsible for administering and overseeing the State's child welfare programs. Effective January 8, 1998, DSS was reorganized into the Offices of Children and Family Services (OCFS) and Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA), within a new Department of Family Assistance. Under the reorganization, OCFS is now responsible for child welfare programs, as well as youth programs formerly under the State Division for Youth. OCFS has also assumed responsibility for the implementation of the CONNECTIONS system. CONNECTIONS is intended to be a single, statewide integrated system connecting OCFS with all 58 social service districts, as well as not-for-profit agencies under contract to provide child welfare services.

The Assembly Committees on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation and on Children and Families focused their examination on the following issues:

Much of the research involved in this investigation was conducted in 1999 and 2000 under the leadership of William L. Parment, then-Chairman of the Oversight, Analysis and Investigation Committee. Initial preparation of this report was conducted under his able guidance. In January 2001, Assemblyman Scott Stringer took over as Chairman of the Committee. Along with Assemblyman Roger Green, Chairman of the Committee on Children and Families, Assemblyman Stringer has assumed the task of completing this report, implementing its recommendations, and helping to ensure ongoing legislative oversight of the CONNECTIONS project. Between the fall of 1999 and the spring of 2000, Oversight Committee staff examined the procurement record and related documents, spoke to State Comptroller and agency personnel, and reviewed various outside reports that cite CONNECTIONS. From initial inquiries and reading through thousands of pages of procurement documents, it became clear that the procurement and implementation processes raised issues that the Committees needed to look at more closely. They decided to hold hearings and make further inquiries. Joint public hearings were held by the Assembly Committees on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation; Children and Families; and Governmental Operations on May 12, 2000 in New York City and May 23, 2000 in Albany. Testimony was received from various users of the system, including: not-for-profit child welfare agencies; county social services commissioners; unions representing State and county workers who use the system; and representatives from the Administration, the contractors, and the State Comptroller's office. The hearings sought to answer the following questions:

This report brings together key issues and findings identified during the Committees' investigation and the public hearings. Some of the testimony received and documents reviewed are quoted throughout this report.20 Most important is understanding the problems with CONNECTIONS and their impacts on children and families. The report will examine this first, and then will try to answer the question: How did we get here? The discussion then goes back to the beginning to consider issues with the original procurement and subsequent contract management. Finally, fiscal impacts of the system are examined. Administrative and legislative recommendations to address these findings are presented, with the hope that similar problems in procuring and implementing future information technology projects might be averted, and to help address present CONNECTIONS problems.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

II. PROBLEMS WITH THE CONNECTIONS SYSTEM AND THEIR IMPACTS ON CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This section of the report summarizes some of the key problems identified with the CONNECTIONS system, and how they have impacted children and families and service delivery. It includes issues and concerns described by witnesses at the May 2000 public hearings, as well as problems that the Committees learned of through their own research. On numerous occasions, the Committees reached out to the Office to understand their perspective on these issues and to learn of their plans to rectify the situation. The focus of the issues raised is: are children better off or worse off since CONNECTIONS was initiated?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

At the Committees' public hearings, representatives of both OCFS and Andersen Consulting touted the successes of CONNECTIONS. It was not until pressed that they admitted what the Administration has been saying for some time privately - that the system is not working as planned. OCFS Commissioner John Johnson testified that he believes the system is currently working. However, his testimony focused on the parts of the system that are operational, rather than functions that have problems or have not yet been put into production. He maintained:

The Commissioner credited CONNECTIONS with reducing New York City's backlog of investigations of child abuse and neglect reports from 31,000 to fewer than 150. He praised CONNECTIONS for improving the amount and quality of information that is relayed from the Child Abuse Hotline to local child protective workers. He also testified that CONNECTIONS has processed over 400,000 reports of abuse or neglect without the loss of a single file. (As will be seen later, many users of the system dispute these claims.) While admitting that the Office experienced challenges in implementing the system, the Commissioner praised the future capabilities of the system, noting that:

Andersen Consulting's Martin Cole also argued that the system is working:

The contractor also credits the system with many functions that are not yet available to users. For example, Mr. Cole noted that the system is designed to help meet State and federal guidelines. Yet it is Release 4 -- which has not been rolled out yet -- that contains many of these functions, including tracking State and federal deadlines and producing federally required AFCARS reports. He acknowledged that while Release 4 was delivered by Andersen in October 1997, it was not placed into production, pending an evaluation of the user test results, an assessment of organizational changes needed, and the resolution of user issues and requests for system modifications. An evaluation of the pilot revealed extensive user dissatisfaction, and as a result, the system was never rolled out. Despite the above positive characterizations, the Administration has admitted elsewhere that the system does not function properly. In June 1999, the Office released a Request for Proposals (RFP) to hire a consultant ("Project Integrator") to reassess the system and determine how to fix it. In this RFP, the Office describes the status of the system:

Further, the proposal from Maximus, the successful bidder chosen by the Office for its expertise, concluded:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

As described above, the problems with CONNECTIONS range from the software and hardware to the overall implementation of the system. This section of the report details some of these problems. It also describes the potentially serious impacts to children and families caused by these problems. The crux of the problem is that only 3 out of the original 5 software releases are operational, and those components that are in place require fixes and modifications. As a result many goals of the system have not been met. Brian Wing, now the Commissioner of the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance, described the problems that CONNECTIONS was supposed to address:

To date, not much has changed. Because of the problems described below, overburdened caseworkers have no confidence in the system. Most caseworkers maintain paper back-up files and have developed cumbersome work-arounds and separate systems to handle what CONNECTIONS was supposed to do. Further, problems such as inaccurate checks of potential child abusers through the Child Abuse Registry potentially put children at risk. Thomas Cetrino, of the Public Employees Federation (PEF), which represents State workers at the Child Abuse Hotline, testified:

Service providers, who generally support the idea of the system, indicate that it is not meeting their expectations. James Purcell, Executive Director of the Council of Family and Child Caring Agencies (COFCCA), which represents most of the not-for-profit child welfare agencies across the state, testified:

While happy about CONNECTIONS' e-mail system, providers more often recognize barriers raised by CONNECTIONS. Some insist that despite these barriers they have been able to serve children as required by law. Others paint a bleaker picture of the direct impact the system has had on service delivery and contacts with children and families. Chautauqua County Social Services Commissioner Edwin Miner testified:

Nicholas Scoppetta, Commissioner of New York City's Administration for Children's Services (ACS), also expressed dissatisfaction with the system:

Several problems were identified with the components of CONNECTIONS used by workers at the State Child Abuse Registry and by local child protective workers investigating allegations of abuse and neglect.

In a recent news article, a Suffolk County child abuse investigator described how it is not uncommon for her memory of a prior incident to be more reliable than CONNECTIONS. In one instance, she was assigned to investigate a case of suspected abuse, where the name of the suspected abuser sounded familiar. She typed the name into CONNECTIONS, but its search function came up with nothing. After searching her paper files, she found that the individual had indeed been reported two years earlier. She noted that such incidents are not uncommon:

These duplicate manual records are in addition to the other manual records needed because the current system is incomplete. For example, CONNECTIONS cannot be used yet for case management and tracking. Therefore, caseworkers enter some information into the old CCRS system, but still must maintain paper files or separate in-house databases for the additional information that CONNECTIONS Release 4 was supposed to track, including federal Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) requirements.

Impacts to children and families resulting from these data and search problems:

A computer system analyst with Suffolk County's Department of Social Services, discussed this issue in a recent news article:

Dr. Russell B. Norris testified about the cumbersome nature of the software, and the experience of the staff of Lutheran Social Services of Metropolitan New York:

PEF members at the Child Abuse Registry also complain about the slowness of the system:

Commissioner Edwin Miner estimated that from 1994 to 1996 (before CONNECTIONS was implemented), caseworkers in Chautauqua County spent on average 1.8 days per week in the office. The rest of the time was spent in the field. From 1997 to 1999, this number jumped to 3.4 days per week in the office, an increase of almost 100%. He explained the reason for the increase:

In March 1998, the Committees on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation and on Children and Families held a joint public hearing on the State's Foster Care System. At this hearing, Commissioner Merrifield testified that as designed, the pilot version of Release 4 was expected to dramatically increase caseworker time in the office even further, rather than cutting it in half as she had hoped. She estimated that in Erie County, time spent on recordkeeping would double from 40% to 80% for direct-care foster care caseworkers if the pilot version of Release 4 were placed into production. This would leave them with only 20% of their time to spend directly working with families and others to move cases along.47 This is part of the reason that Release 4 has not yet been implemented.

Impacts to children and families due to the slow and cumbersome system.

Over 14,000 CONNECTIONS computers and other related equipment was initially provided by the State to local districts, contract agencies, and State workers at the Child Abuse Registry. The equipment was allocated based on the number of caseworkers that were expected to use the system directly. Thereafter, if an agency wanted to expand its operations or give system access to non-caseworker staff (e.g. support staff or financial personnel), it was required to purchase the equipment at its own expense. A description of some of the key computer hardware problems that were identified during the Committees' review follows.

This has proven detrimental to agencies trying to provide services to families, particularly in New York City where a Neighborhood-Based Child Welfare Services initiative (discussed below) is being instituted. James Purcell of COFCCA testified on this issue:

Since the May 2000 hearings, the Office has begun moving forward in the area of equipment purchases and moves. Committee staff has been told that a Request for Proposals (RFP) has been developed for additional equipment purchases, maintenance, and site moves. A contract is anticipated to be in place in early 2001. In the meantime, the Office has been providing users with some old, refurbished CONNECTIONS computers. The Office has also contracted with several other vendors to do installations, site surveys, and moves.

After many frustrating months of correspondence with State and ACS staff, Lutheran Social Services finally received replacement equipment recycled from another agency. However, the agency only received half of what they originally had, the software on the machines was not upgraded, and the machines were missing keyboards and mice.60

Diana Farkas of St. Christopher-Ottilie described the delays experienced by her agency:

Impacts of insufficient CONNECTIONS computers

Many problems relating to the CONNECTIONS software were identified. Too numerous to list in their entirety, some of the key issues raised and their impacts follow.

An example of such statutory changes is the far-reaching federal Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA), and the corresponding State enacting legislation (Chapter 7, Laws of 1999), which require child welfare providers to meet numerous new deadlines and requirements. The State's child welfare information system should be expected to help document and track many of these requirements. However, so far, only a few changes have been incorporated into system "Builds". Other needed ASFA changes have not yet been made, as they mostly relate to case management which is part of Release 4. Further, new federal regulations establishing performance measures required under ASFA will undoubtedly require additional changes to the system. The Office has informed Committee staff that State workers use a manual process, involving data from the old Child Care Review Service (CCRS) system, to meet the ASFA requirement for tracking the time a child spends in foster care. This information is then posted to the local districts. Some districts use this data; others track it on their own through databases they have developed or purchased specifically to meet ASFA requirements.

Workers must still depend on other State databases that are not integrated with CONNECTIONS -- such as CCRS and the Welfare Management System (WMS) - to provide information not available in CONNECTIONS. This requires more time and effort by caseworkers, and involves duplicate data entry. In many locations, workers must log on to at least 2 computers on their desks to access the various separate databases. James Purcell of COFCCA testified:

Commissioner Merrifield stressed the importance of integrated information systems:

Not only will linking various State systems help improve service delivery to children and families, but it was one of the federal requirements of SACWIS systems.

The Office has informed the Committees that State staff and Maximus staff are in the process of developing a "data warehouse" that will enable local reporting. This will replace what Release 5 was supposed to do. However, a system to enable local reporting is not expected to be available statewide until the end of 2001 at the earliest. In the meantime, local districts and agencies have been left to their own devices -- at their own expense. In New York City, ACS has taken the initiative to expand on the existing canned reports. Among other things, ACS and Andersen Consulting (the original developer of the CONNECTIONS software) designed a separate system for management reporting. Commissioner Scoppetta testified:

While this work appears to fall within CONNECTIONS' original goal of improving management information and decision making, ACS had to do this additional work on its own.

Impacts of software deficiencies

Following are some examples of inadequacies in the planning and implementation of CONNECTIONS that may have contributed to the problems with the system described above.

State and county workers that use the system also complained that they have not been involved in designing and fixing the system. Thomas Cetrino of PEF testified:

Mary Sullivan, representing CSEA workers in the counties, had this to say about the latest efforts to fix the system:

This lack of user input helps to explain the dissatisfaction among users with Release 4. Because their needs were not adequately considered, the product that was delivered by Andersen Consulting did not represent what the users thought they would be getting, and what, in fact, they needed to execute their responsibilities. As will be discussed in more detail later, it appears that in trying to limit the number of modifications to the Texas system, Andersen Consulting and the State dropped some of the requested changes or "gaps" identified by users as necessary to fulfill State requirements. The heavy involvement of the Governor's office from the beginning, rather than the State agency which is more familiar with the needs of users, certainly affected this result. A November 1998 State Comptroller's audit of CONNECTIONS found that system users were not adequately involved in system planning and testing. The audit charged that these weaknesses resulted in delays, user dissatisfaction, and escalating costs. Commissioner Johnson acknowledged the impact of this early lack of user input, noting:

The Office has acknowledged that it must gain user support in order for the system to succeed. Such a requirement has been documented as vital by a recent study of SACWIS systems in other states.76 The Governor's Review and Oversight Panel, formed in response to the audit, issued recommendations in 1999. Based on these recommendations, the Office has put into place a management structure that is intended to involve users -- at both the front line and management levels -- in improving and developing the system. This structure includes an overall Steering Committee, a Management Committee, and several work groups focused on topical areas. The Committees heard from several witnesses that are pleased with this structure so far. Deborah Merrifield, Erie County Social Services Commissioner, testified:

Despite the positive attitude of some users, the past experiences, low morale and skepticism of others may continue to be a barrier to successful implementation. There is still a feeling among front-line workers that the Office continues to ignore their concerns. The unions representing caseworkers that use the system every day in the local districts and the Child Abuse Registry report that their members are not involved with the recently formed committees and workgroups. And some question whether the Administration is truly interested in hearing about the problems that they are experiencing.

She believes it is important to scale back expectations to complete the project, concluding:

Chautauqua County Social Services Commissioner Edwin Miner echoed these sentiments:

Commissioner Merrifield commented that although many of the current priorities were part of the original concept of CONNECTIONS,

In fact, the formal goals of the system have changed over time. While the initial RFP for the system outlined the basic federal SACWIS requirements -- meeting federal reporting and data collection and integration requirements, and providing more efficient, economical and effective administration of child welfare programs -- the system was gradually expected to do much more. In December 1996, a Reform Plan developed by New York City's Administration for Childrens' Services (ACS) anticipated that CONNECTIONS would help to significantly improve operations at the troubled agency. The system was expected to reduce the agency's reliance on 26 different, unconnected computer systems that required a redundancy of paperwork. It was also expected to "empower caseworkers with the tools they need to do their jobs, and create a positive work environment for workers while improving their efficiency and productivity." 82 Additionally, as will be discussed, the Office has invoked the CONNECTIONS system in more recent years as the answer to numerous programmatic deficiencies cited in Comptroller audits. The Office has recognized that the goals for CONNECTIONS must be streamlined to get the project under control. In response to the Governor's Panel recommendations, the goals have been revised and improved to reflect user-driven needs, which focus on serving children and families and supporting basic casework practice in addition to fulfilling technical requirements. Among the goals are supporting local flexibility and access to data, creating better quality case records that reflect accurate data, and eliminating unnecessary data entry and forms.

Dr. Russell B. Norris, Jr. of Lutheran Social Services of Metropolitan New York, told of calling the help desk several times with a hardware problem and being told different things each time. He concluded:

Thomas Cetrino, of PEF, told of Hotline workers' frustration:

Diana Farkas, Personal Computer Manager at St. Christopher-Ottilie, complained that the help desk is very slow and many staff are inexperienced:

OCFS explained to Oversight Committee staff that when a problem requires a modification to the software, the ticket is entered into a database. An OCFS management team sets priorities and decides whether to incorporate these tickets into the next software "Build". As of November 2000, there were 1,038 unresolved tickets, out of almost 4,000 received since the project's inception.87 The large number of unresolved problems further supports user claims that the system does not meet their needs.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

In March 2000, the State Comptroller issued several follow-ups to 1997 audits of the State's child welfare programs. The Office had originally cited CONNECTIONS' future capabilities as solutions to the audit recommendations. For example, the Office had promoted CONNECTIONS' planned ability to generate detailed management reports, and to track information about children in foster care and those freed for adoption, as ways to increase monitoring of State programs. However, these case management and reporting functions are part of the non-operational Release 4 and the "Data Warehouse" that is currently under development. In the follow-up audits, the Comptroller noted the continued unreliability of CONNECTIONS, and criticized claims offered again and again by State officials that CONNECTIONS is the "answer" to many of the audit recommendations:

A recurring recommendation in the follow-up audits was that, until CONNECTIONS is fully operational, other steps should be taken to improve monitoring in areas relating to: the Adoption Subsidy Program (audit report 98-F-27), Kinship Foster Care (audit report 98-F-25), and Adjustments to Welfare and Food Stamps Benefits to reflect placements in foster care (audit report 99-F-24). Specifically, the Comptroller recommended the State perform formal monitoring of district compliance through actual district site visits. Until such formal monitoring is done by OCFS or its regional offices, it is impossible to know whether State child welfare programs are being implemented as required. Thus, children that are intended to be helped by these programs may not be receiving needed services.

Two recent court settlements cited in the Committees' earlier joint report, LOSING OUR CHILDREN: An Examination of New York's Foster Care System, underscore the need for a properly functioning child welfare information system. The first settlement is of a federal class action lawsuit brought on behalf of children in the City's child welfare system, against New York City and State child welfare officials (Marisol A., v Rudolph W. Guiliani). The plaintiffs asserted widespread failures by the City and State to adequately protect and serve children in the New York City child welfare system. Among the charges was that the City's case records were incomplete and did not adequately reflect services that may or may not have been provided. In December 1998, settlement agreements were reached with the City and State. These settlements were to expire in March 2001. Under the City settlement, an independent Advisory Panel was created to assess ACS' performance and issue recommendations and timetables for improving services and agency administration. Such efforts continued through December 15, 2000. Several of the Panel's recommendations highlighted areas where the implementation of an up to speed and comprehensive CONNECTIONS system would be particularly beneficial, especially in measuring performance indicators of the child welfare system as a whole, and in monitoring ACS and contract agency staff performance and outcomes. The Panel noted in its Final Report that such performance measurements of front line and supervisory practice would be hampered rather than aided by CONNECTIONS, as currently designed:

The Panel explained the importance of knowing differences in performance at the individual staff level as a critical step in strengthening front line practice in the child welfare system, and concluded:

The State settlement, among other things, required OCFS to:

In January 2001, the plaintiffs went back to the court seeking to enforce the State settlement and to extend the settlement period to ensure that all provisions are met. The plaintiffs were not satisfied with the State's compliance with the settlement provisions, including the requirement to use reasonable efforts to implement CONNECTIONS. In their Memorandum of Law in support of their motion to the court, they stated:

The second suit (United States ex. Rel. Graber v. The City of New York, et. al.), settled in November 1998 by the City and State, alleged that City officials developed a plan whereby caseworkers filed false casework reports on hundreds of children in foster care, without providing the needed services. The settlement required the City and State to pay back $49 million in federal foster care dollars. In addition, it required the City and State to provide detailed information to the federal Administration for Children and Families (ACF) regarding compliance with State and City foster care laws and policies. Notably, once the CONNECTIONS child welfare computer system is finally implemented, the Office is required to provide ACF with a computer terminal so it can access data on foster care cases. This appears to be another instance where lack of oversight and incomplete case records have resulted in penalties to the State. Until CONNECTIONS is fully functioning and can help detect fraud and abuse, the State runs the risk of continued exposure to such actions.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Administrative

Legislative

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In light of problems and issues raised about CONNECTIONS, the Committee on Oversight, Analysis and Investigation went back to the project's beginning to try to answer the question: How did we get here? This necessitated understanding the procurement process, and the resulting contracts with IBM and Andersen Consulting. Committee staff reviewed thousands of pages in the CONNECTIONS procurement record and other documents, including a bid protest on file at the Comptroller's office, and requested clarification from the Office when needed. The review sought to answer: Did the agency follow the Procurement Stewardship Act and other laws in letting the CONNECTIONS contracts? If so, did the Act itself contribute to some of the problems which resulted? If it was not let in compliance with the Act, how and why not? Where did the process break down? Does the procurement record clearly disclose steps followed and decisions made in the procurement process, as the law requires? Did these actions lead to some of the problems with the system today? Does the CONNECTIONS procurement offer any lessons on how the Act might be improved? This section first discusses the State's technology procurement process generally, and then lays out findings relative to the CONNECTIONS procurement.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

As mentioned earlier, the purchase of computers and information technology, as well as other goods and services purchased by State agencies, is governed by the State Procurement Stewardship Act (the Act)92. This law, originally enacted in 1995, was modified and extended in June 2000. The awarding of the CONNECTIONS contracts, which began in late 1995, was governed by the Act. A basic principle of the Act is to ensure fairness, transparency and objectivity in conducting State procurements. It is also intended to promote competition and avoid favoritism among vendors. The law states: "The objective of state procurement is to facilitate each agency's mission while protecting the interests of the state and its taxpayers and promoting fairness in contracting with the business community." 93 While lowest price is the basis for awarding contracts for commodities or goods, the 1995 Act established the principle of "best value" for purchasing services, including information technology and computer hardware. Best value procurements seek the offerer which optimizes quality, cost and efficiency, and give agencies greater flexibility in selecting a proposal which best meets their needs. To help ensure the fairness and transparency of State procurements, agencies are also required to maintain a Procurement Record identifying -- with supporting documentation -- the decisions made and approach taken in the procurement process. The National Association of State Purchasing Officials' (NASPO's) Principle and Practices suggest that "the documentation ought to be sufficient to allow competing bidders or offerors, the public and the press, and auditors the basis for the award decision….After award, the procurement file should contain a record sufficient for a reader (perhaps some considerable time later) to follow the course of the transaction, especially as to the method of evaluation and basis of award."94 Based on provisions of the Act, State agencies have established procedures for conducting best value procurements, including issuing Requests for Proposals (RFP's) and evaluating proposals received. Many of these procedures are detailed in Guidelines issued by the State Procurement Council.95 The process described below, which DSS set up to determine best value in the CONNECTIONS procurement, is similar to that which State agencies typically use for other best value procurements.96

DSS issued an RFP in July 1995 to potential vendors. This document laid out the minimum technical specifications that vendors were required to meet in order to be considered responsive. It also set forth general criteria against which the proposal would be evaluated, and set a maximum score that could be achieved. DSS established a Technical Evaluation Committee (TEC) first to identify detailed evaluation criteria and document them in the procurement record before offers were received, and then to evaluate, score and rank the proposals received based on these criteria. The scoring of these individual criteria were also documented in the procurement record and summarized and tabulated in charts. Such an arithmetic scoring system enables a potentially subjective assessment to be quantified, and lends credibility and objectivity to the process. Proposals were to be ranked based on the total points received. The agency also set up a Financial Evaluation Committee (FEC) to evaluate the price proposals and determine which offers were within the competitive range established before offers were received. Proposals were to be ranked based on total costs, including certain additional costs the FEC determined would be incurred by the State to implement each proposal. The TEC and FEC were comprised of agency personnel with expertise suitable to make such evaluations. These committees operated separately from each other; neither committee knew the issues raised or rankings given to the proposals by the other committee until the end of the process. After offers were received and evaluated, the TEC and FEC were to submit reports including the rankings and their recommendations to an over-arching Selection Committee. The Selection Committee included management level personnel from DSS, plus non-voting representatives from the Division of Budget and the State Comptroller. It was charged with evaluating the recommendations of the TEC and the FEC and making a final recommendation to the DSS Commissioner. The process originally established for the CONNECTIONS procurement is a fair characterization of how other agencies are to conduct best value procurements. However, some of the changes DSS made in the CONNECTIONS procurement may have had an impact on the problems that subsequently occurred in the design and implementation of the CONNECTIONS system. Therefore, lessons to be drawn from the way the process was followed in this case have implications on other procurements in the State. As will be seen below, in numerous instances the established process broke down, in disregard of the intent and spirit of the law. Some of these issues were the subject of a bid protest filed with the Comptroller's Office by Unisys Corp. Unisys was a partner with BDM Technologies Inc., one of the bidders in the CONNECTIONS procurement. It should be noted that currently there is no statutorily required process for vendors to follow in contesting the fairness of a procurement and resulting award. NASPO recommends that procurement statutes require a procedure for resolving protests, complaints and contract disputes.97

B. FINDINGS RELATING TO THE CONNECTIONS PROCUREMENT

Numerous documents related to the procurement, through the year 2000, reveal direct involvement by the Governor's office in key decisions and project management relating to CONNECTIONS.

As discussed earlier, it is not clear from the Procurement Record who made key decisions in awarding the CONNECTIONS contracts. This information had to be gleaned from affidavits submitted in response to the bid protest filed by Unisys. According to these documents, final decisions on awarding the CONNECTIONS contracts to Andersen Consulting and ISSC were made by George Mitchell, an appointee of the Administration, rather than then-Acting DSS Commissioner Brian Wing. Mr. Mitchell had previously been involved in several large technology procurements in other state agencies. On November 16, 1995, Mr. Mitchell was appointed Deputy Commissioner for Systems Support and Information Services for DSS. Commissioner Wing stated in his affidavit:

In fact, Mr. Mitchell became involved in CONNECTIONS even before his appointment was official. On November 15, 1995, he became Chair of the CONNECTIONS Selection Committee. According to his affidavit, he made key decisions which were not documented in the Procurement Record:

Mr. Mitchell was also the driving force in recommending the split bids in the Best and Final RFP:

Ultimately the Selection Committee, led by Mr. Mitchell, recommended awarding the contracts to ISSC and Andersen Consulting. The procurement record does not indicate who the Selection Committee report was sent to and who signed off on it. This information is also not included in the affidavits. What is clear is that Commissioner Wing had little to say in the final decision. It appears as if the Governor's Office and the Division of Budget played a stronger role in the decision than the Commissioner. Mr. Mitchell described the process:

Commissioner Wing confirmed his lack of involvement in the procurement. In fact, he described his role in the decision-making process as "ministerial":

Without clear responsibility, there can be no accountability. This is a concern in the CONNECTIONS case, where it has been difficult to ascertain who is accountable for the cost-overruns and the fact that the system does not work as intended. What is clear is that it was an appointee of the Governor's office who claimed responsibility for the decisions that overrode the quasi-scientific, arithmetic methodology of the Technical and Financial Evaluation Committees. The end result was a procurement based less on clear, discernable factors, and more on factors that were constantly evolving -- sometimes with little apparent rationale or supporting documentation.

After the procurement, it appears that the Governor's Office was less directly involved in the early stages of project implementation during 1996-1998. At least, such involvement is not apparent in records made available to the Committee. However, in response to a stinging November 1998 State Comptroller audit, the Governor's Office convened a special review Panel--external to DSS--to evaluate problems with the system and make recommendations on how to proceed. Clearly, the Executive saw the project drifting and took back the helm. In March 1999, the Panel issued recommendations which included, among other things, appointing an internal Project Manager who would report to the Governor's Office. The Panel also recommended competitively contracting with an outside consultant, or "Project Integrator", to provide quality assurance, help manage the contractors and state workers developing the system, and assess whether to modify the existing software or start over. Both recommendations were implemented by the Administration. The outside consultant is under contract with OCFS, but reports directly to the Governor's Project Manager. In fact, the Committees learned that OCFS had only a non-voting role in evaluating and selecting the successful bidder, Maximus. Instead, the Evaluation Committee was headed by Project Manager Zachary Zambri, who reports to the Governor's Office of State Operations. It is clear, therefore, that not only did the Governor's Office intervene to try to get the project back on track, it continues to be heavily involved in the project.

It is not necessarily inappropriate for the Governor's Office to be involved in a project of this size and complexity, particularly given the problems that exist. In fact, the current involvement of the Executive has been helpful in getting the project back on track and responding to users' needs. However, it is essential that the Administration make known who is responsible and why. This will help answer questions about the project that can be traced back to the procurement (e.g., the decision to split the award), in the hopes of avoiding similar problems in future procurements. Unfortunately, the procurement record leaves unanswered even the most basic question: Who was responsible for making the final decision in the procurement? Despite the ongoing involvement by the Governor's Office, no one in the Administration today can speak to the entire history of the project. Anticipating this problem due to high turnover among project staff and the restructuring of the agencies, the chairs of the three Assembly Committees sent a letter to the Director of the Office of State Operations before the May 2000 hearings. They made it clear that the hearings would include a comprehensive discussion regarding the project history and management, and that they "hope and expect that the Administration's representatives at the hearing will be able to fully speak to these issues."129 At the Albany hearing, Commissioners Wing and Johnson, and Project Manager Zambri, appeared together to answer the Committees' questions. While collectively they answered many questions, they could not answer some very fundamental ones. In particular, they could not provide clarification on decisions made in the procurement process, the reports issued by the TEC and FEC, and even details of the first amendment to the Andersen contract worth $28.5 million. This is troubling as these are areas that appear to be linked to problems with the system today.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Administrative

Legislative

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IV. CONTRACT MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION

A necessary outgrowth of the Committee's examination of the CONNECTIONS procurement was to understand the process by which vendor contracts were negotiated and implemented and the Office's management of the project as a whole. The goal was to gain further insight into how some of the problems with CONNECTIONS arose, and to learn from past mistakes to avoid them in future technology procurements. The Committee's inquiry involved an extensive examination of the original contracts with ISSC and Andersen Consulting, related change orders and contract amendments, and planning documents submitted to the Federal Department of Health and Human Services. Meetings and discussions with representatives of the Administration, State workers, the Federal Government, and the Comptroller's Office were conducted. In addition, several witnesses at the public hearings discussed project management issues they had encountered first hand. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

From the start, the Financial Evaluation Committee (FEC) warned DSS that hiring two vendors and placing the State in the role of project coordinator was a risky and potentially costly endeavor. As a result, the FEC recommended against awarding the project to two vendors. This position supports the belief held by many that one contract with one vendor is easier to enforce than multiple contracts, where lines of responsibility may be blurred. In hindsight, the FEC's predictions have proven all too true. First, contract costs have almost doubled with no end in sight. Second, the State has become an intermediary between two vendors, making it difficult to hold either accountable. Third, a lack of commitment by the administration to provide adequate staff resources dedicated to the project has resulted in yet another consultant being hired to fill the State's role and regain control. There was also a general lack of clarity in the contract requirements--particularly for the software application--that created misunderstandings between the State and the contractor when the product was delivered. The result was confusion and delays, and possibly costly change orders. The State Comptroller's audit of CONNECTIONS noted the following deficiencies in project development and implementation:130

In an October 1999 follow-up audit, the auditors found that the Office had implemented many of the audit recommendations, including convening stakeholders and improving controls. But, since few changes have been made to the system since 1998, it is too early to tell what the end result will be. The Administration recognizes some of these past mistakes. Project Manager Zachary Zambri testified:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

The RFP specified that the CONNECTIONS procurement was to result in a fixed-price contract with specific hardware and software deliverables. The RFP did allow that if the State altered the scope of work, causing an increase or decrease in the contractor's effort, it would negotiate with the contractor to arrive at a price adjustment and actions to be taken. Under the negotiated contract price of $37.5 million, Andersen Consulting was to provide a SACWIS system-- known as CAPS--which it had developed for Texas' centralized child welfare system, plus a fixed number of days' work (5,448 days) to modify it to fit New York's needs. On its face, it appears that the contract called for a specific product at a fixed price. However, a question that was not directly addressed was: what if the specified number of days were not sufficient for Andersen to adequately tailor the system to meet New York's needs? According to Andersen's financial proposal: "Our Best and Final price offer reflects our assumption that the State will agree to work with us to limit modifications to only those essential changes which can be delivered with approximately the effort included in the proposal. This equals 1,406 days for SCR Intake, 2,596 days for Case Management, and 1,446 days for the Financial Management initiatives. We believe that this effort is more than adequate to make the necessary modifications to CAPS to meet your requirements. Any non essential changes or enhancements identified during the pilot or statewide rollout would be deferred until the system is in production statewide."132 The negotiated contract does provide for payments for ongoing application software maintenance based on hourly rates.133 This provision opened the door for further scope of work changes.

It turns out that DSS and Andersen severely underestimated New York's requirements and the changes that would be needed to make Texas' state-administered system work for New York's decentralized operation. Shortly after the contract was signed, DSS and Andersen convened a group of users from around the State to review the Texas system and identify "gaps" between what the users perceived they wanted and how the base software operated. A total of 811 gaps were identified. The work involved to incorporate all 811 changes far exceeded the allotted 5,448 days, so the State reduced the number of gaps to be addressed to 326, reflecting only those items DSS deemed most critical.134 The work effort involved to implement these 326 items, plus additional requirements to conform to changes in State law and to meet unique needs of New York City, still far exceeded the original 5,448-day limit. The excess work then became the basis of a 1997 contract amendment totaling $28.5 million.135 Martin Cole, Managing Partner at Andersen Consulting, testified at the Committees' hearings about the extent of the work involved in this first amendment:

This amendment notably changed the agreement from a fixed-price contract to one based on time-and-materials. According to the amendment: "Actual effort spent over and above the 5,448 person-days will be billed separately to the State by Andersen…" 136 The amendment specified hourly billing rates for time spent to perform the work. It also provided that any additional scope changes after the initial release of CONNECTIONS would again be covered by the contract's application software maintenance provision, on a per-hour basis.

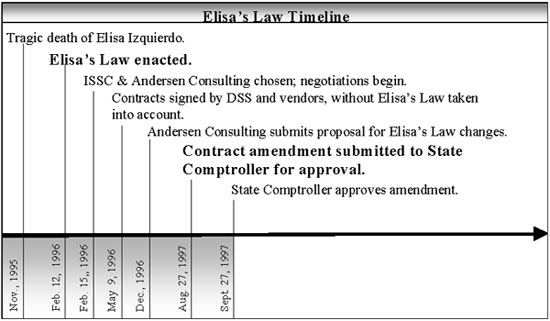

The first amendment included, among other things, programming to ensure the system is in compliance with New York State's Elisa's Law (Chapter 12, Laws of 1996). This law made significant changes to procedures used by the State Central Registry of Child Abuse and Maltreatment (Child Abuse Registry) including the length of time reports to the registry must be kept, access to confidential records, and other statewide policies and procedures. DSS knew that Elisa's Law would require changes to CONNECTIONS as described in the RFP. Although the original proposals were already being evaluated at the time Elisa's Law was signed, the impact of the new law certainly could have been, and should have been, considered at the time of contract negotiations. The National Association of State Purchasing Officials (NASPO) has stated regarding post-contract changes: "In no case should a vendor be promised before award that the performance requirements will change in its favor after the contract award. Additionally, solicitation performance requirements should not be changed during contract performance except through an authorized change order to the contract, and only where the change does not materially alter the nature of the contract, and could reasonably have been within the contemplation of the parties at the time it was awarded." 137 Elisa's Law was enacted on February 12, 1996, shortly before the vendors were selected and contract negotiations began. The original contract with Andersen Consulting was not signed until May 9, 1996, and was not approved by the Comptroller's office until September 1996 -- six months after Elisa's Law was enacted. All along, the State and Andersen knew that additional work would be necessary to integrate Elisa's Law into the Texas system, but the State failed to notify the Comptroller's office of the pending contract increase. Although the parties knew about Elisa's Law, the final contract amendment was not drafted by Andersen until December 1996. This was submitted to the Comptroller on August 27, 1997 -- 18 months after the law was enacted. It appears that Andersen had been working on the needed changes for some time before that, however, because 95% of the work requested by the State was completed by the time the contract amendment was submitted for approval. The cost to incorporate Elisa's Law was $5,467,472,138 an increase of 15% over the original contract.

This work could have been part of the original contract negotiations, and hence, the work could have begun earlier. At the very least, the agency should have assessed the impact of Elisa's Law up front as soon as it could be determined. Then it could have put the Comptroller's office on notice that a change order increasing the contract pending before it would be coming. Not providing such a courtesy to the Comptroller creates the appearance that the agency was not forthright.

Although amendment #1 included 326 of the gaps between the Texas system and New York's needs, this represented only 40% of the gaps identified by users during the design and planning stage. This contributed to user dissatisfaction with the system; many have said that the system delivered does not reflect what they thought they were getting. Further, problems with Texas' software were carried forward by Andersen into New York's system. Despite early visits to Texas by New York State officials to learn about problems Texas encountered in implementing the Andersen software, the Comptroller's auditors found many of the same problems persist in New York's system.139 The Comptroller's audit has called into question whether some of the work billed under amendment #1 should have been covered by the original contract:

In response, Commissioner Johnson acknowledged the shortcomings of the change order process, and promised that revised procedures would be implemented. The October 1999 follow up audit, however, found they were only partially implemented.141 The Office has indicated that Maximus has assumed the role of evaluating proposed change orders, their prices and the goods and services received. In 1999, in accordance with the Governor's Review Panel's recommendations, the Office convened major stakeholders and system users to identify critical Release 2 and 3 fixes needed to make the parts of the system already in place functional. In early 2000, several contract amendments were proposed totaling $34 million, bringing the contract total to over $100 million. While some of the work involved was new, much of it was intended to eliminate significant "work-arounds" that child welfare caseworkers had developed out of necessity because the system still did not meet their needs. Despite the significant additional work being performed by Andersen, the system will still not be complete when they are done. Release 4, the biggest part of the system, is still not operational, and the Office does not yet know how much effort and money will be involved in completing it.

As designed, CONNECTIONS was supposed to produce biennial reports to the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) on key foster care and adoption statistics. This was a key requirement of the RFP, and one of the principal goals of CONNECTIONS. The Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) data was to have come from information gathered in Release 4 of CONNECTIONS. Andersen Consulting says that as delivered, Release 4 does meet AFCARS reporting requirements, as well as National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) requirements. Because Release 4 is not yet operational, complete data are not being reported as required. As a result, New York has been assessed $3.3 million in federal AFCARS penalties to date, and faces an additional $817,000 for the second half of federal fiscal year 1999-2000. The State will continue to be non-compliant until Release 4 or its replacement is implemented, facing annual penalties of $1.6 million. New York, along with several other states, is appealing the penalties assessed to date. At the time this report was written, the appeal had not been resolved. Until then, HHS has placed the penalties on hold.

The various liability provisions of the original contract between DSS and Andersen Consulting were vaguely drafted, and included a jumble of cross-references and apparent inconsistencies. Consequently, assessing the State's possibilities for legal recourse against Andersen is difficult, at best. But, it is fair to characterize the problems with the contract's liability provisions as generally working to the detriment of the State. Following are some of the problems with the original contract:

Despite the many problems with the CONNECTIONS system and the urging of the federal government, the Office has not sought to recoup damages from Andersen in accordance with provisions of the contract. This in part can be attributed to the weak position the State was in as a result of the original contract language. The Office did withhold payment on invoices submitted by Andersen in 1998 and 1999, because of questions as to whether the contractor had adequately delivered the agreed-upon system. One of the contract amendments entered into by the State and Andersen in 2000 included a settlement of the outstanding invoices and changes to the liability provisions of the contract. Because of trade-offs that were made, the State may be in a better position to enforce the contract, but barely so. It is difficult to identify the dollar impact of the liability changes made, particularly because it appears that the Office didn't make a precise assessment of the risks and possible rewards of litigation. In negotiating the terms of the original contract and subsequent amendments, it appears the State was being led by the vendor, who has more expertise in negotiating complex computer technology contracts. State Comptroller H. Carl McCall, whose office is responsible for reviewing all contracts over $15,000, recently commented on this problem:

There is clearly a need for the State to improve its ability to negotiate and manage complex technology contracts. This is especially important in light of recent large information technology initiatives the State has committed to (e.g., OTDA's Welfare Management System, and the Department of Health's Medicaid Management Information System), as well as other large computer projects the State will continue to enter into in the foreseeable future. While the Administration's Office for Technology (OFT) has recently initiated programs to help negotiate and manage such projects, these efforts do not go far enough.

Andersen Consulting used a computer programming language -- owned solely by Andersen -- known as "Foundation for Cooperative Processing" (Foundation) to aid in design of the CONNECTIONS software. Andersen developed Foundation for use in designing systems for its customers. However, few other consulting firms used it at the time Andersen was selected to build CONNECTIONS. The State has obtained a license to use Foundation as part of its contract with Andersen, but few State workers are trained to use it. The use of Foundation has proven problematic to the State in several ways. Requirements by the Federal Government and the State Legislature that additional work be competitively bid caused the State to look for others that could work in Foundation. In 1999, the State conducted a Request For Information to find firms or individuals that could continue work on CONNECTIONS. No firms were found to be able to provide a significant number of programming staff skilled in the use of Foundation.144 This has left the State in the position of potentially hiring Andersen as a sole-source contractor to finish the work simply because no one else can do it. Because of the historical problems described above, this would not be the preferred choice. Further, the Federal Government has indicated that it will not approve such an action. In correspondence to the Office, ACF states:

The State Legislature has also required that State funds for additional developmental work will only be made available after a competitive procurement. However, it appears that even if an RFP is issued, Andersen Consulting may be the only vendor able to bid. An alternative is to train State workers to do the job. The Committee is aware that the Office is in the process of hiring and training computer professionals to maintain CONNECTIONS once Andersen's contract runs out. While cautiously optimistic about this effort, it remains to be seen whether the new staff would be ready in time to do the additional developmental work.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

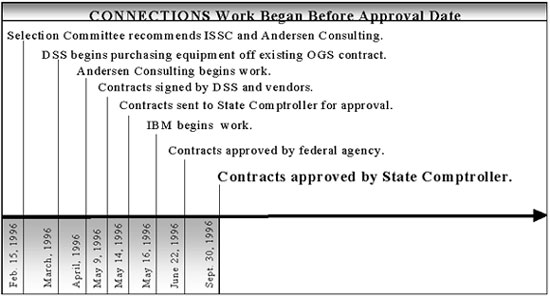

As mentioned earlier, the State locked itself into buying IBM computer equipment before the contract was signed by the parties and approved by the Comptroller. In March 1996, DSS began buying IBM equipment through a centralized State contract. Then, between May and August 1996, ISSC - an IBM subsidiary -- completed statewide rollout of equipment worth $60 million under the CONNECTIONS contract, prior to Comptroller approval. By that time, using IBM equipment was a fait accompli. Furthermore, the contract signed with ISSC only allowed IBM machines to be certified on the CONNECTIONS network. This has precluded the State from buying additional equipment from other vendors, using a competitive bidding process. It was not until the fall of 1999, when the federal Administration for Children and Families pressed the Office to use a competitive process to procure additional equipment, that the Office required IBM to certify other vendors on the network.